“I work in Toronto but I live in Georgian Bay.””

If, on a lovely summer day, you were to return to the ojibway after many years away, you might think at first that it hasn’t changed very much at all. Even if it had been 50, 60, 70 years since last you saw it, the impression that the old place gives – the dock, the tower, the gabled roofs, the crest of trees – would accord with distant memories. The façade of the hotel itself has been altered very little since 1913, when the last expansion of the main building was completed. The central stone steps and the main veranda have been there since the hotel’s very earliest years. Inside the hotel, the birch railing on the stairs is as it always was.

Plaques with the names of regatta winners line the walls along the Ojibway’s main staircase.

The reality, of course, is that it has changed, and the most obvious difference is that the people who once embodied the Ojibway – the people who once were the Ojibway – are no longer there. Bert Bruckland and Albert Desmasdon are not on the dock anymore. Hamilton Davis is not pausing on the stairs to have a word with his wife before she hurries to the kitchen to make sure the cook has remembered how Judge Carpenter and Dr. McKenna like their fish prepared. For many of the guests of long ago, it would be impossible to imagine the place without Mrs. Davis. Her real name was Irene, but she preferred “Lou.” She could be as stern as it might be imagined an Irene could be, but she always had a Lou’s twinkle in her eye.

But some of the changes would be less obvious. There are cellphones and fax machines today, of course. These are givens. But it wasn’t long ago that telegrams for islanders came into the railway station and were brought out to the hotel by Reid’s Boat Service. Bert Bruckland would get one of the guides to row the message out to the recipient’s cottage. For some years, the Ojibway had a radio phone and it offered a 24-hour message-delivery service to islanders. Albert Desmasdon, who oversaw delivery, had a phone in the family cabin so he could hear it ring, whatever the hour. His son Joe recalls having to go out once at about four in the morning. It was terrible weather: rain, wind, thunder, lightning. “Dad would send three of us,” Joe remembers, “at that hour.” And so it was that the Desmasdon boys ended up pounding on the door of a cottage near Shawanaga Bay in the pitch dark. When the cottager eventually roused himself and opened the door, he stared in disbelief at the “drowned rats” before him. He took the message, read it and then said to the boys: “What in the hell did you bring this for?” It was from his ex-wife. Apparently, he was late with his alimony payment.

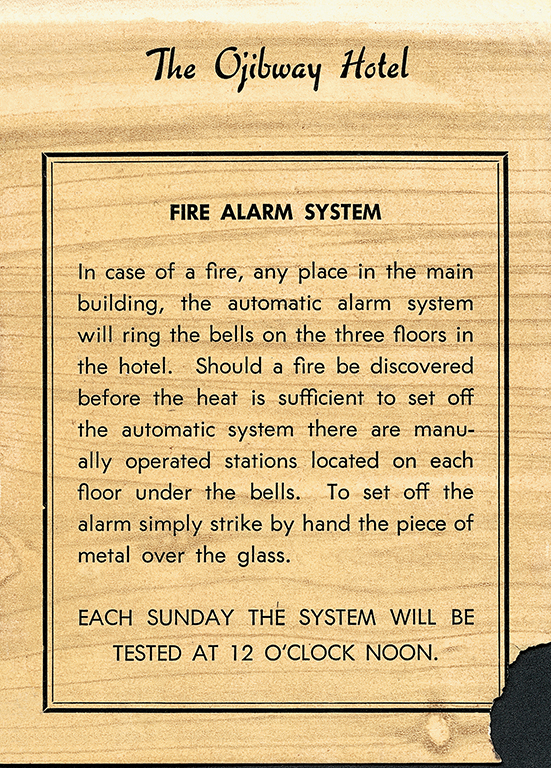

Never to be underestimated, Georgian Bay is famous for its weather. Sudden gales and three-day blows can play havoc with boats and docks, and when the thunder begins to rumble, lightning strikes and resulting fires are always a possibility. Miraculously, the Ojibway never had a serious blaze, even though a fire alarm system was not installed until the 1950s.

Today, there is a modern sprinkler system, but 50 years ago buckets of sand were stationed at the end of the hotel’s corridors and in the stairwells – in case of fire. Somehow, they never had to be used. But still, the Ojibway looks much the same – and it’s amazing, actually, that this is so. It’s a miracle that it never burned to the ground.

There were a few close calls. In the early 1950s, Maplewood almost went up in smoke when some steel executives from Ohio kept their fire so constantly stoked that the stone of the fireplace got hot enough to set the wooden wall ablaze. Fortunately, the butcher was an old navy hand. He knew to keep the doors of Maplewood closed to prevent oxygen from feeding the fire until a bucket brigade was organized and the pumps got going. The fire was quickly extinguished while the guests, oblivious to the drama, finished their baked lake trout in the nearby dining room.

Fifty years ago, the ice for refrigeration was cut from the bay in winter and stored, beneath a coating of sawdust, in the ice house. Since then, propane fridges were introduced, and later electrical refrigerators, run by generators at first and, eventually, by hydro.

For the first 60 years of its existence, the Ojibway kept its focus on fishing. No other activity came close in importance. Until well into the 1960s, knowledgeable fishing guides who knew the shoals and bays of the area like the back of their hands were a critical part of the hotel’s daily life.

By the 1950s, steamers, such as the Mazeppa (right) – offering the “finest freshwater trips in the world,” according to the North Navigation Company – were visions of the past. Increasingly, families travelled to Pointe au Baril by automobile and made use of their own small outboards to get to their cottages and to the Ojibway.

Back then, the fishing guides used to sit in a line along the edge of the east end of the dock, by the wooden rowboats, waiting for their customers to come down from the hotel. They would have been as common a sight as the City of Dover pulling into the wharf on its daily run from Midland. In the days when the steamers were still running, the passengers would shift over to the leeward side if the passage had been windy and rough. The big old boats sat high in the water and were of fairly narrow beam, and the combined weight of the huddled passengers would tip the steamer on an angle as it made its stately way toward the Ojibway dock.

But the City of Dover had its last run in 1950. The steamer service from Midland, Penetang and Collingwood ended altogether in 1952. There are smaller boats now, of course. Lots of them. Everyone has one. Or two. Or three. Today, on an ordinarily busy day at the Ojibway, there are zippy little whalers, slow and steady Smoker Crafts, brand-new Scouts, leaky tinnies and sturdy Limestones. These are the boats that deliver the many kids to the recreation program for the day. Now, the children’s program has become the very pulse of the place.

A hundred years after Hamilton Davis opened the Ojibway for business, the myriad boats that regularly tie up to its dock are testament to the hotel’s continued popularity.

Over the years, the number of courts has increased, and, without doubt, the quality of the surfaces has steadily improved (above). But what has remained constant, whether for fierce competitors or more easygoing players, is the popularity of tennis at the Ojibway.

It used to be that there was only one tennis court – and it wasn’t exactly Wimbledon. Joan Roberts, who played on the University of Toronto tennis team in the 1930s, recalls childhood games at the Ojibway on a court made of “grass sticking up through mud.” Now there are five good courts. In the 1960s, an islander named Goldie Fleming took it upon himself to raise the money to install a modern court at the club, thus ensuring that tennis continues to be part of summer life at the Ojibway. Les McHattie and Peter Stewart, regulars on the Ojibway courts for many years, set standards in their day that are still seldom matched. The former Governor General, Roland Michener, played his last game there in 1990 – at the age of 90.

These days, on summer mornings, the men gather early at the Ojibway for their matches. They play until the newspapers are delivered, and then they settle on the front porch, for coffee and conversation. The women players arrive for their round robins soon after the men have retired from the field of battle, and by then the resident fox snake has emerged from its hole at the southeast corner of court number two, to find a warming ray of sunshine. The pok-pok

of well-hit forehands and backhands, the genial congratulations of “Good serve” and the emphatic

calls of “Out!” that filter through the pines from the interior of the island are as they always were. Sometimes you can close your eyes and be transported back 40 years. But the tennis shoes look nothing like the plimsolls of old. No one wears the yellowing V-necked tennis sweaters anymore. There are no wooden Slazenger racquets, no Dunlop presses, no white tennis balls.

Times have changed, and someone coming back to the Ojibway wouldn’t see the families that had once stayed there, summer after summer: the Thurbers or the Kerrs or the Ellises. There are no waitresses in their yellow uniforms and their aprons on the veranda of the hotel. Miss Cowan, the head waitress, isn’t there. Nor is Miss Morgan, the postmistress. Calvin Noganosh isn’t heading out in the iceboat to make his frequent deliveries to cottagers’ iceboxes.

They come in old boats with new engines, and new boats with old engines, and everything in between. But they come. And every August, the Ojibway dining room turns into an art gallery for three days where over 50 artists show their work. The Ojibway Art Show remains one of the summer’s most popular events.

But Gordon Bongard and Gary French are on their way to pick up their newspapers at the store. They are chatting with Phyllis and John Porter. Up the old stone steps, on the veranda, the Lords and the Marleys are having breakfast. The place is buzzing – with activities that were unheard of 50 years ago. Pilates and fitness classes, the Parent and Tot Play Group. There is even a book club.

Bridge survives as an Ojibway tradition. The watercolour classes, organized by Carol Prior and Rich Cavers, are always popular, and since 1963 the Ojibway has celebrated the work of Georgian Bay artists with one of its most popular events. Evoy’s water taxi unloads the wooden crates of oil paintings, watercolours and drawings for the Annual Ojibway Art Show. The club’s big aluminum boat pulls away, loaded with cardboard and paper and tins and bottles, on its way to the recycling depot at the station. Bob Murray’s yellow seaplane passes in the cloudless blue sky overhead. A cluster of cottagers on the dock frowns at a passing pair of Jet Skis. And the handsome wooden hull of the Orvisses’ Zipalong noses gracefully into the dock for a landing.

Fifty years ago, there was a stable that housed the hotel’s milk cow in the summer and the horses that hauled ice in winter. “Throat easy” Buckingham cigarettes were sold in packets of 10 for 10 cents and 50 for 50 cents at the Ojibway store; Weston’s “English Quality” biscuits, shaped like maple leaves and called “Canucks,” were available; and Fly-O-Cide and Skeeter Skatter were the bug repellents Mr. Davis recommended; and Botany wool, cashmere and angora sweaters were sold at the Ojibway gift shop in “form-fitting, glamorous colours.”

Holidays at Pointe au Baril and at the Ojibway were not fast paced and not crowded with events. Things moved slowly. Swimming parties, picnics, canoeing, sailing races – all provided opportunities for families to relax and get together.

It was a different world, and Doris Scott, who first came to the Ojibway with her family before the Second World War and who recently returned for a visit, remembers swimming at the front dock and picnics out on the islands, and she remembers her father. He went fishing every day. She remembers the dance pavilion out back. There were dances on Wednesday and Saturday nights, and the five-man orchestra – four of whom were members of the Ojibway staff – liked to play “Honeysuckle Rose” as often as they could. There was chapel on Sunday mornings and singalongs at the piano in the evening. She remembers the young islanders coming to the dock to pick up mail and groceries. Shyly, she had introduced herself to a few of them that summer – because there were not many young guests at the hotel – and she remembers being invited to a wonderful party out at the cottage of the Mathews family: “An afternoon party with lunch and lots of fun and games.” That day, she counted 27 boats there – a sunny, happy afternoon of laughter and splashing and suntanned bodies and smiling faces that was once so vividly present it would have been impossible for her to imagine a day when, sitting on the veranda of the Ojibway, she would say that the Mathews party had been 68 years earlier. Doris is now a petite, animated woman with thick white hair, but she was a 15-year-old girl with shoulder-length brown hair the last time she was at the Ojibway.

Sixty-eight years earlier, the young woman then known as Doris Dodds had a crush on Bee Mathews. “He didn’t know. But he was so nice.” Still, it was Jack Griggs who gave Doris her first kiss, on her last holiday at the Ojibway. “It was a romantic place,” she says. “It just kind of grabbed you.”

Doris remembers meeting the Sinclair girls, Peggy Aird, the Kelks and Marion Collins. She was introduced to Hugh Hall and to the Greene family from Cincinnati. But probably, of all the things that Doris Scott could have said about the Ojibway, the most remarkable is what she observed when the old place first came into sight that day: how little it has changed over the years.

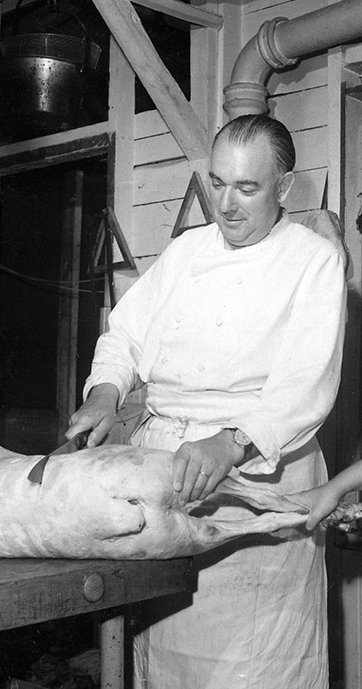

At the Ojibway’s first store on the dock (bottom, right) guests could purchase postcards, crafts and souvenirs. Later, the hotel’s gift shop, located in the tower, boasted a more sophisticated inventory. The hotel’s butcher provided islanders with their favourite cuts of meat.

Over the decades, the function and location of some of the smaller buildings have been altered. What is now the gift shop had been the site of a grocery store, an ice-cream stand and a tuck shop. For a while, it had a fully equipped meat counter where, despite the butcher’s enthusiasm for snorts of Teacher’s and 7Up, islanders came to purchase steaks, ribs and roasts, which were then wrapped in brown waxed paper and tied with string. Bert Bruckland and Albert Desmasdon established their headquarters in the old hardware store, and there was always a slow, steady stream of islanders and guests who needed to speak to them about hiring a guide or buying a lure, fixing an outboard or renting a boat. For a while, the gift shop was in the base of the Ojibway’s tower: “English and Scotch woolens, Irish linens, Chinese china and lingerie, Mexican jackets, Italian bags, Quebec handicraft, Indian rugs, boxes and moccasins” – all were available there.

For many decades, the ice house sat squarely on what is now the path to the tennis courts. It was an ordinary wooden shed – no more substantial than the simplest cabin and without any form of insulation – and yet it was one of the most important buildings in Pointe au Baril. Until propane refrigerators were introduced to the area, the ice house supplied the hotel’s kitchen with much-needed refrigeration and kept many cottagers’ iceboxes solidly cold – as opposed to uselessly melted. Some of the island ice boxes were so thermally challenged that they required almost daily deliveries from the Ojibway, and the iceboat, and the solid blocks of sawdust-covered ice that it delivered were among the most common sights of a Pointe au Baril summer.

Seagulls continue to scout the skies at the Ojibway, but times have changed. Nowadays, they’re after leftover sandwiches from the snack bar instead of castoffs from the old fish-cleaning station.

A smaller ice house, located below the tower on the steep inclined path the bellhops called “Hell’s Run,” was used exclusively by the butcher. Baby-beef steaks and roasts and spring-lamb legs, chops and loins, as well as French Roquefort cheese and old Stilton were available at the butcher’s. Behind what is now the grocery store was the constantly busy fish-cleaning and filleting station. It was a smelly job (according to the waitresses who were asked by the fish cleaners to dance), but it earned the young men who worked there excellent tips.

The fish-cleaning station was also very popular with the gulls. They perched themselves in a row across the peak of the Ojibway’s roof – not a sight that Hamilton Davis liked very much.

Bellhops and porters were usually kept busy, but if Hamilton Davis ever found them idle, he made them go out to the front of the hotel to collect the white feathers that constantly drifted down from the gulls lined on the roof. But there aren’t many gulls on the roof anymore. The fish-cleaning station is long gone.

Walter Lloyd-Smith worked as a bellhop for a few summers. The bellhops delivered ice and firewood to the cabins. They hauled garbage out to the incinerator tucked downwind from the hotel on a back bay. They ran the loads of delivered coal up from the dock in old wooden wheelbarrows, for the laundry-room water heaters, and Walter Lloyd-Smith recalls that 400 pounds was the record for a single load.

The bellhops also moved mattresses from cabin to cabin. At that time, there were six cottages, three on each side of the main building of the hotel. The paths linking the cottages were rough, and replacing single beds with a double, at the request of a guest, could be a trying affair. Alan Thomas, who worked summer jobs at the Ojibway as a teenager, remembers how he and another bellhop were struggling at an awkward point on the path when his partner slipped down a rock face, followed by a cascading double spring. Brushing himself off, the boy looked up to Alan and said, “Ain’t love grand?’ ”

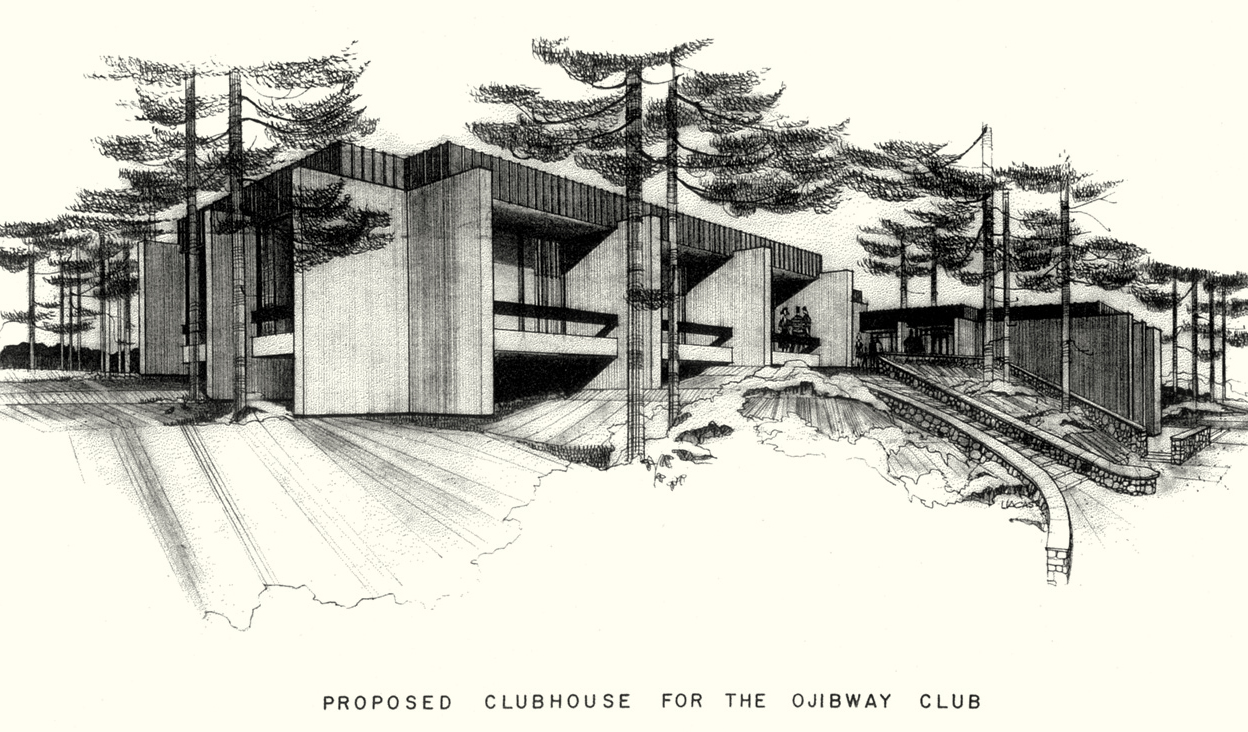

Whether caused by the slow erosion of time or by sudden calamities such as the small tornado that destroyed the porch at the base of the tower (above right), the Ojibway’s constant need of repair was a cause for concern to its directors. By 1971, the cost of maintenance had reached the point at which consideration was given to tearing the old building down and building a new clubhouse altogether (above).

Somehow, the Ojibway never burned. But there were times when it started to look as if it might just fall down. In the early 1960s, when the expenses of maintaining a 60-year-old structure had become particularly daunting, some consideration (serious enough for Pentland and Baker Architects of Toronto to have been hired to produce preliminary drawings) was given to demolishing the Ojibway altogether and replacing it with the concrete and glass of a low, stylishly modern clubhouse. And there were times in the 1960s and 1970s when the Ojibway Club’s board of directors – facing the crunch of rising costs and declining revenues – were obliged to discuss such radical measures as removing the second and third floors of the old building entirely.

In 1960, Peter Bryce was employed at the Ojibway’s grocery store, and by 1971, at the age of 25, he was the club manager. The generators were constantly breaking down. His ears were attuned to their constant rumbling, and the minute they fell silent he had to run to pull-start the auxiliary engine that, in turn, started the bigger motor. His right hand still bears the scars from yanking the pup engine’s cord. “But the club is about individuals all the way along,” he says. “Each picked it up and carried it along.” And this is how – sometimes against all odds – the Ojibway continued. As Peter says: “There has always been someone who has kept things going.”

As well, over the years, changes have taken place within the organization itself. There was never any physical indication of these transformations – the Ojibway was always the Ojibway – but on June 8, 1959, the Ojibway Club was incorporated. Guests continued to come to stay at the cottages, but the focus had shifted to the interests of the islanders. The club’s stated objectives were “to promote, and provide facilities for sporting, social and community activities, among the summer or permanent residents of the islands.”

The decision to transform the Ojibway from a hotel to a club, like the decision in 1942 to purchase the hotel from Hamilton Davis, helped avoid the fate of so many of the big old summer hotels. By the postwar years, it was clear that their day was over, and most of them were left to mercies far less tender than the Ojibway’s. In the early 1960s, not far to the south, boys from Camp Hurontario wandered through the ghostly abandoned hotel at Copperhead near Sans Souci – a place that had once been just as established, just as successful and just as much a fixture of the community as the Ojibway. Copperhead’s broken windows, mildewed old books, empty corridors and ripped screens were the very image of the future that the foresight and generosity of a dedicated group of cottagers managed to prevent for the Ojibway.

No less significant a change was the long-sought designation – initiated by the board and approved by Revenue Canada in 2001– of the Ojibway Historical Preservation Society as a registered charity. Perhaps more than any other change, it assured the Ojibway’s future. Several million dollars have been raised from the Pointe au Baril summer community to renovate, refurbish, repair, repaint – to preserve the Ojibway.

It’s no accident that the Ojibway was never abandoned, never left derelict. It’s no accident that to anyone returning after a long absence, it would look as pristine and well kept as always. It still looks like the success it was when Hamilton Davis ran it, even though it has been through some difficult times.

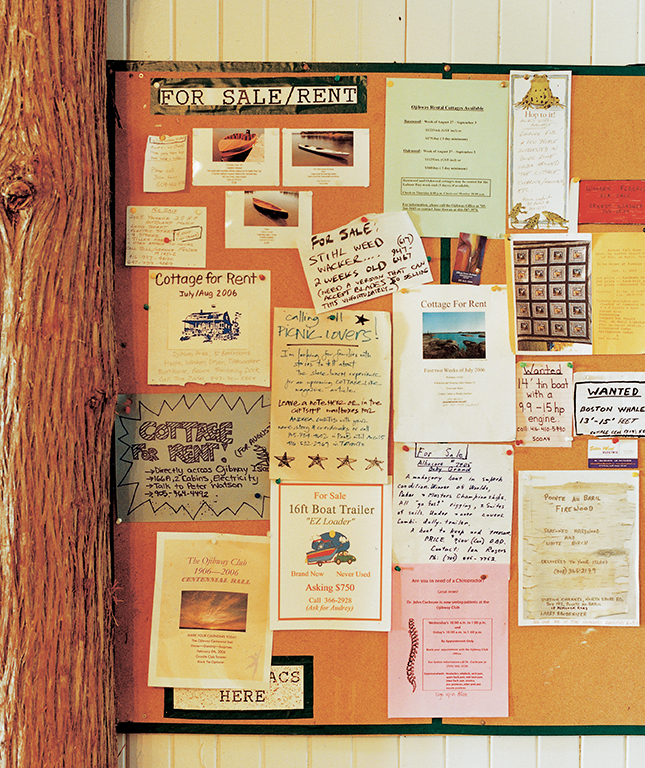

At the Ojibway’s office, islanders can exchange information on the bulletin board or pick up a romance or adventure story. Many of the old books still bear the stamp inside the cover: “The Ojibway, Pt. au Baril Hotel Co. Ltd., H. C. Davis, Mgr.”

Over the years, the music that was played at the Saturday dances every week of every summer at the Ojibway changed from foxtrots and cha-cha-chas, to big-band jive, to crooner waltzes, to the twist, to rock and roll. On the secluded back beach, the ladies’ bathing attire evolved from the clammy cotton of dark full-cover tops and knee-length bloomers to Esther Williams’s one-piece, to the first shocking sightings of an itsy-bitsy, teeny-weeny yellow polka-dot bikini. For 50 years, Bert Bruckland ruled the dock – “yarning” with anyone who stopped by for a chat – and then, in 1956, Bert retired. For 44 years, Albert Desmasdon ran the Ojibway’s boat works and maintenance service until the late 1960s, when he moved his operations to the mainland to establish a marina. For many years, Napoleon Longlade – kind, charismatic and handsome – was the most sought-after Ojibway fishing guide, and then, on a strange, sad afternoon in June of 1973, a boat leaving the gas dock churned up what staff had thought to be an old sleeping bag floating under the surface of the water. It was Napoleon’s drowned body.

A bathing party on the back beach of Ojibway Island (above) in the hotel’s early years; a somewhat more crowded and less modest affair (above right) in the 1950s; and one of the fixtures of many an Ojibway summer – the popular guide, Napoleon Longlade (right).

Time passed. Telegrams, the radio telephone on the Ojibway dock, and then fax machines, and then cellphones, and, eventually, the Internet would replace the long-established tradition of mailbags delivered by Evoy’s and then sorted in the post office, a little cabin on the path between the grocery store and the tower. Islanders had their own numbered mailboxes, and many would come every day for letters and magazines and The New York Times or Chicago Tribune. In the early 1970s, Ann Doritty, who worked there with Ann Porter, remembers that it was “a really old-fashioned post office.” Everybody wrote letters in those days – wives to husbands who were spending their weekdays in the city; parents to children away at camp; teenagers to their heartbreakingly absent boyfriends and girlfriends – and everyone came to the Ojibway post office to drop off and pick up their mail.

From the beginning, the Ojibway had been a kind of recreational and community centre for everyone in the area. Chapel services, fishing guides, the dining room and groceries were all available to the cottage community. Often it was the availability of ice cream that was the biggest draw, particularly for the children. In the days of inefficient iceboxes and temperamental propane fridges, ice-cream cones at the Ojibway were a real treat.

The hotel’s laundry room was, for many cottagers enjoying their summer holidays, a welcome luxury, although there were some, apparently, who viewed it as more of an emergency service than a weekly amenity. Joy Wright, who worked in the laundry room at the Ojibway in the late 1930s, remembers one gentleman who arrived at the hotel, three sheets to the wind, and then calmly waited outside in his boxers until his white trousers were cleaned, dried and pressed.

From the day Hamilton Davis opened the Ojibway’s doors, it’s been a focal point of Pointe au Baril. Islanders have always relied on it for news, for supplies, for services and for the sheer fun of going to the hotel.

The regatta may be the competitive highlight of the summer, but the fundamental skills of swimming, sailing and canoeing were taught throughout the summer at the Ojibway. Water safety was a concern, and swimming lessons were taught on the back beach by Mary Campbell Richardson in 1948. Diving lessons on the front dock were given to those who wanted to perfect their jackknives and swan dives or simply soak everyone with a perfectly executed cannonball. In the early 1970s, canoeing was taught by Rob Thorburn – “a purist,” Ann Dorrity remembers, who’d learned his J-stroke, feathering and bow-rudder techniques at Birnie Hodgetts’s Camp Hurontario near Twelve Mile Bay. Canoeing had long been regarded as exactly the kind of activity that should be taught to young people at the Ojibway. In 1963, club president Douglas Deeks wrote in a letter to islanders: “Canoeing lessons, I think, are extremely valuable, as today with the great growth of outboard motors, very few children grow up knowing how to paddle a canoe properly. This is noticeable even in the senior regatta, when some of the canoeists have to paddle alternately on both sides of the canoe to keep it straight on course.”

While the regatta has been a summer feature of Pointe au Baril since 1907, with the junior regatta added in 1927, lessons in swimming, diving, canoeing and sailing, all held at the Ojibway, have been no less important to the islanders. In an environment where the knowledge of how to handle a boat properly, how to swim and the fundamentals of water safety and life-saving can be much more than mere recreation, the Ojibway has played a role in making sure that young people are equipped for their summers in Georgian Bay.

There were times when these kinds of programs were popular, and times when they were not. During the 1960s, for instance, young people had other things on their mind. In the minutes of the Ojibway Club’s annual meeting in August 1963, Bill Joyce, head of the sports program, reported: “Only fair attendance at classes, the common complaint of the instructors being that parties seem to take precedence over attendance.” Not even the Ojibway’s weekly movies were immune to the cultural divide that had erupted between the generations. When the controversial film Easy Rider was shown at the Ojibway one summer night in 1973, parents grumbled, but the audience, composed largely of teenagers who made the movies a weekly ritual, were pleased that the “Ojib” had become so hip.

The Ojibway’s popular swimming lessons continue today.

Its popularity rose and fell. It was busy at times, then empty. It was cool for some years, square for others. And yet the seasons continued to turn. Summers came and went. Regatta ribbons pinned on rafters of old cottages faded. And the present – like the long-ago time when a boy gave a 15-year-old girl with shoulder-length brown hair her first kiss at the Ojibway Hotel – continued to do what it always does: it kept slipping into the past. The boat traffic increased, the fishing declined. The winter ice and the ever-changing water level of Georgian Bay continued to play havoc with cribs and docks.

The next generation: The Ojibway may look stately and antique and dignified, but the energy and enthusiasm of the people who have always used it most make it clear that it remains young at heart.

And although the façade of the Ojibway looked much the same, 1971 was the last summer the dining room stayed open. Mitzi Thurber, who had first come to the Ojibway as a little girl in 1940, continued to rent Elmwood long after the Ojibway ceased to rent rooms in the main building, and she remembers receiving a “chilly” note from management abruptly announcing that meals would no longer be served in the dining room. The summer of 1971 was also the last time the butcher opened shop, with his brown craft paper, his white string and his hidden bottle of Teacher’s.

In 1972, Doug Hall took over as manager, and the place, he says, was in “bad shape.” The gas dock was operating at a loss, and the bank in Parry Sound was keen to have a $20,000 loan paid off. Bill Mosley, a member of the Ojibway Club’s board of directors in the late 1960s and early 1970s, remembers that the physical plant was in constant need of repair. He wrestled with old generators and once, establishing new standards of hands-on directorship, got out the ropes and helped haul a new one to the generator house behind the hotel.

Until hydroelectricity came along, the Ojibway always required two generators. “A larger one and a smaller one,” Mosley recalls. “The smaller one was used at night. The big one was used during the day for refrigeration. We had to have a backup generator because if one gave up – which it did – we couldn’t pump gas, couldn’t pump water, couldn’t pump sewage, couldn’t use the cash registers, couldn’t have refrigeration. Electricity was vital for that place.”

But over the years, the technological challenges of a summer in Pointe au Baril were overcome. Hydro was introduced in 1975 and electrical lines were run over the island. As well, demographics began to swing back in favour of the Ojibway. Islanders, many of whom had enjoyed the club as children, returned to their Pointe au Baril summers, now as parents. And there, as if on cue, was the Ojibway, ready to step back into their lives. New families arrived and quickly became part of the fabric of the community.

The Ojibway, it’s true, looks much like the man who built it in 1906, Hamilton Davis. It is stately, impressive and dignified. And yet, at the same time, it has the same youthful soul it’s always had. It’s always as carefree as a pretty waitress named Araby Lockhart who, in the late 1940s, loved to organize staff performances for the guests on Sunday. It is as calm as Napoleon Longlade, who, on a summer day in 1965, peered from the Ojibway dock, divining the wind and the weather and reckoning where the bass would be biting that day. Somehow, the Ojibway has a way of holding on to time, and on to the people who pass through it.

The Ojibway’s swimming, sailing, boating and tennis program steadily grew until, by the 1980s, a daily camp and a full-scale recreation program was in place. The program was a success, ensuring that the Ojibway continued to be the centre of activity, from dawn to dusk, for the next generation.

The steady passage of time, the summers upon summers of guests and visitors, the wild Georgian Bay storms – all have worked away at the Ojibway. There were periods when it was allowed to age, but it always put on a brave face. But just when things were beginning to look as if they might never return to the standards Hamilton Davis originally established, someone always stepped in to help it, to preserve it and, on more than one occasion, to save it.

Children grew up and went away – to college, to travel, sometimes to war. Then, eventually, they returned to Pointe au Baril, introducing their own children, and then their grandchildren, to what Hamilton Davis built a hundred summers ago. The dippies and rowboats have been replaced by outboards and tin boats. Fountain pens have given way to keyboards. The old iceboxes have vanished and the kerosene lanterns now sit on stone mantels as decorative antiques. And throughout all this, the Ojibway has carried on. It’s miraculous, really: that on a well-chosen island, just inside the outer shoals of the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, there remains a place as constant as the prevailing wind, as familiar as a perfect summer day.