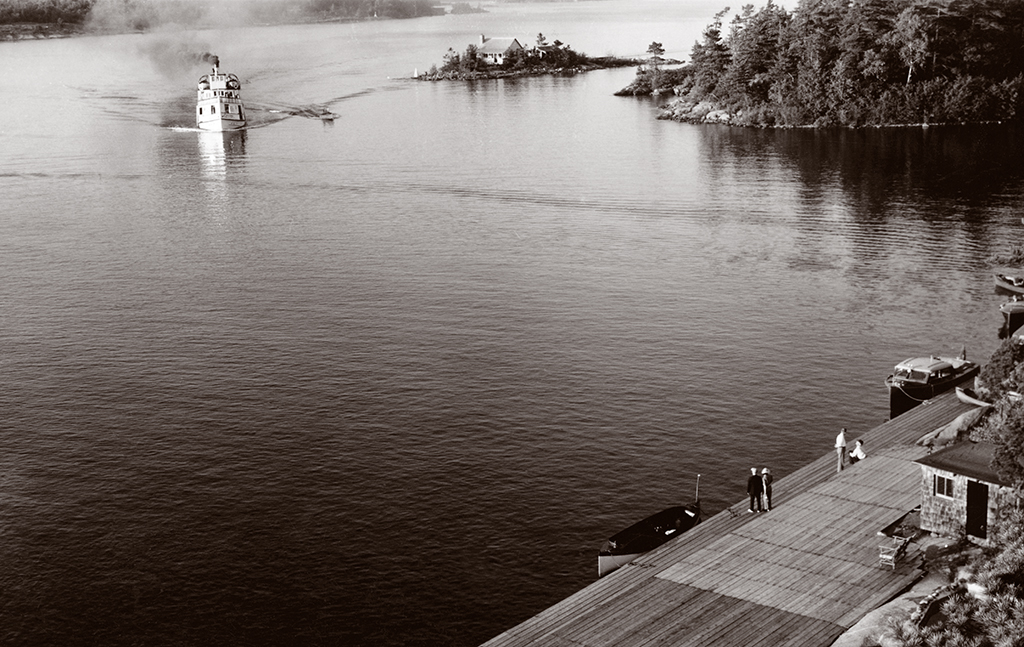

“Part promenade, part loading platform, part landing point for stately steamers, the wharf was the focal point of hotel life at the Ojibway.””

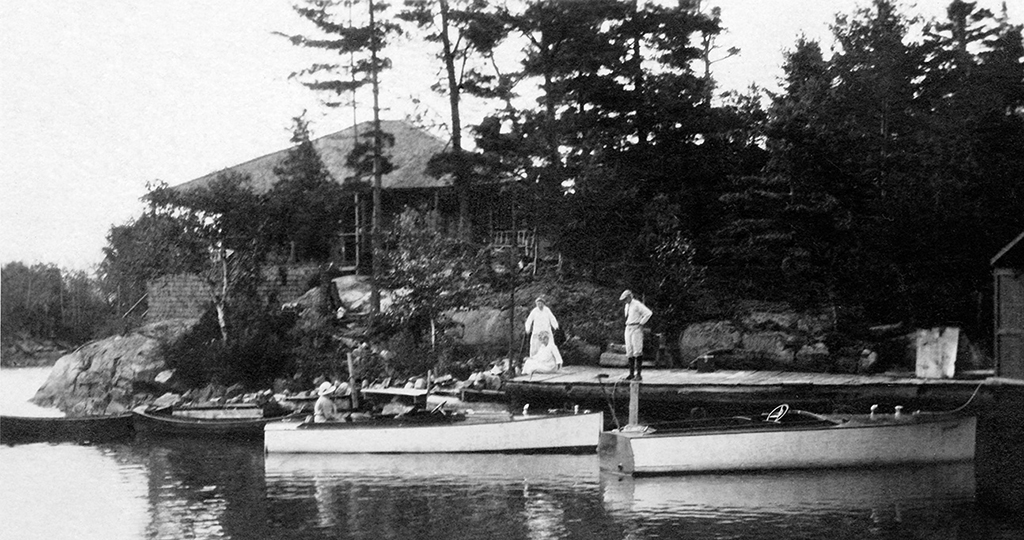

In the early years, it was not called “the dock.” it was simply the wharf and it was built for the purpose of receiving the large steamers that plied the eastern shore of Georgian Bay. The Waubic, Mazeppa, Britannic and Midland City delivered supplies and mail to the Ojibway. Arriving hotel guests were also often on-board, and when they were, Hamilton Davis and his first wife, Millie, could be seen descending the hotel’s stone steps as the steamer’s lines were being secured. Hamilton, who was most often found behind his desk in the hotel’s lobby, felt that it was important to greet guests personally, and it was on the dock that the cordial owner-manager shook gentlemen’s hands, and his wife extended a gracious welcome to the ladies.

In 1908, the steamer Cara provided daily service between Parry Sound and the Ojibway for a fare of $1.50 return.

The 50-foot Waukon, operated by the Reid family, offered leisurely boat trips out from the Ojibway dock in the 1920s and 1930s.

Hamilton probably met Amelia “Millie” McIntosh through his friendship with her brother, Jack. The family owned and operated the McIntosh boarding house, which was just south of the Bellevue Hotel. Millie and her sister Addie, a schoolteacher, were taking in guests, many of whom were friends and patients of their sister Isabel, a nurse working in the United States. In her diary, May Bragdon described the sisters as “very pleasant and attractive.” Evidently, Hamilton agreed. He married Millie in Pointe au Baril on September 17, 1907.

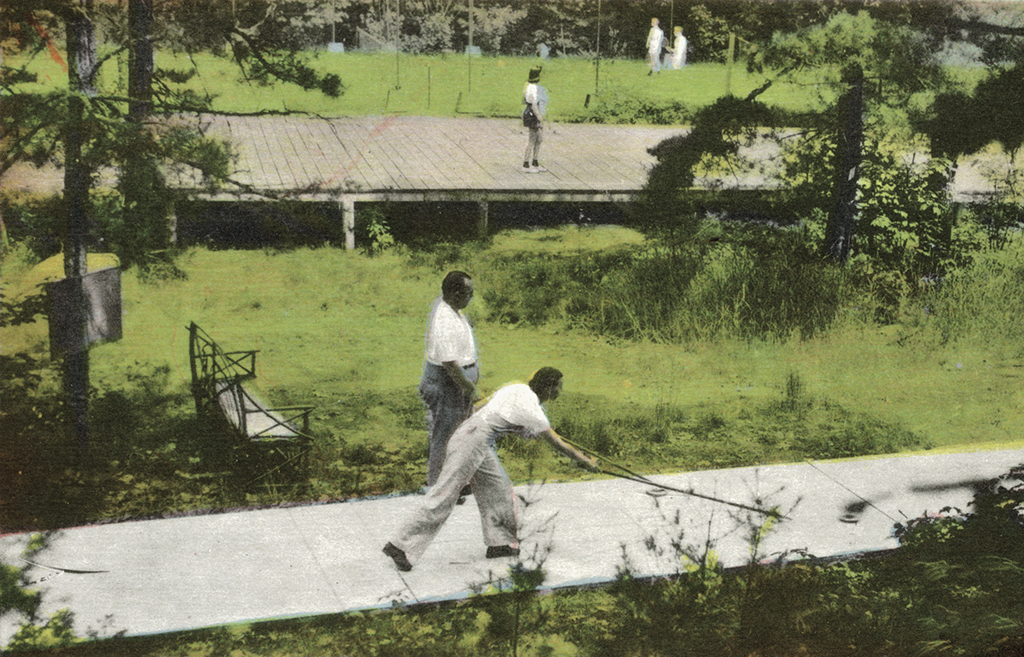

Once hotel guests had settled in, they were invited to explore local channels and islands in one of the Ojibway’s comfortable launches (left), featuring cushioned seats and elegant awnings which protected fair complexions from the sun. More adventurous guests could ply the waters on their own, enjoying the majestic scenery of Georgian Bay from the less-shaded and not-quite-so-comfortable seats of one of the hotel’s rowboats (top).

On the dock, Millie and Hamilton gave departing guests particular attention, for they always hoped that a holiday at the Ojibway Hotel would become a summer tradition, and for many, it did. People often came year after year. The guests were often serenaded by staff – a little ominously, it might have been imagined – with “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” as their boat slipped away from the dock.

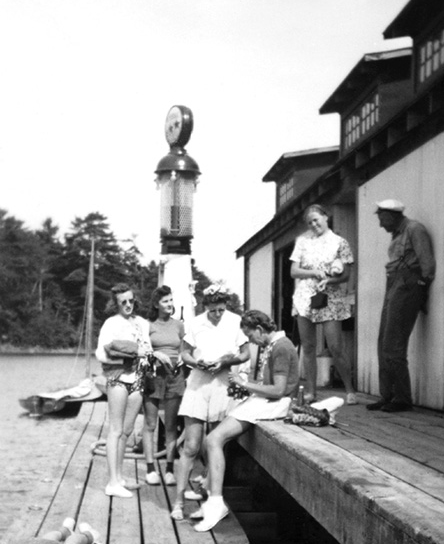

The dock was central to summer life. Not only was it the place where the steamers arrived regularly, it was a place that the hotel guests held in common with many islanders. Guests stood on the dock, strolled on the dock, sat on the dock, sunbathed on the dock and swam at the dock, but even so, islanders always felt that it was a welcome landing where they could tie up. Islanders came to the Ojibway for mail, for groceries, for ice and for a newspaper. Cherry pies, for 30 cents each, were made by the hotel’s chef and sold there to cottagers. Plain York chocolate bars were a nickel each. Ice cream was a draw, especially for children. So was cold soda pop. The Ojibway dock was all very exciting.

“One evening,” cottager Bill Mosley recalls, “we paddled down in a canoe to see the City of Dover come in. That was big entertainment! We had to get dressed up. We couldn’t go down there looking like bums – we put our good clothes on because at the Ojibway, they dressed up in the evenings. The dock was full of ladies in their long dresses and the men in their jackets and ties, strolling up and down. The Dover was unloaded and there were two cardboard boxes for us! My uncle had sent up tomatoes. One box was quite ripe and the other was less ripe, so it could ripen while we ate the first box. We had a lot of tomatoes.”

Sometimes islanders came for information. As a child, Bill Mosley used to accompany his mother when she came to the Ojibway for the mail and groceries. He remembers following her up to the office where she would ask to see the hotel register “to see who was there.” The big book was placed before her and she perused the pages closely to see how many of the guests she knew.

The dock was the village green. It was the town square. It was the common. The regattas had always been held there. Once, the dock was polished with Spangles wax beads for the regatta dance. It was always the most obvious place for islanders and guests alike to meet. Almost inevitably, “See you at the Ojibway” meant see you at the Ojibway dock. It was even used by some as a gauge of the weather. If it had rained during the night but the Ojibway dock was dry by 11, the weather would turn fair. If it was still wet, the outlook was not so promising.

Guests often came to the Ojibway in groups of old friends from the city, or else found new company at the hotel. Either way, the same parties were inclined to return for the summer, year after year.

When the first telephone booth appeared on the dock, men lined up there, reading newspapers and waiting for their turn to check in with the offices that were somehow managing without them. In snapshots taken of summer holidays at Pointe au Baril – whether taken by islanders or guests – the most common setting is the dock of the Ojibway Hotel. A staff member recalls one regular guest, an older, slightly eccentric gentleman, who would have breakfast with his wife, and then make his way down to the dock to see what was going on and who was there. He stayed for the whole day. He made it his job to tie up every boat that came in.

Even pranks by hotel staff took place on the dock. In the 1960s, Frank Penfold was working at the Ojibway. His uncle Alf Sawyer was the hotel’s manager at the time, and Alf became concerned with what appeared to be the blurring of the line between the boys’ and girls’ sleeping quarters on the third floor of the hotel. Apparently, Alf decided to make an unannounced visit to the girls’ rooms one night – a move that sent several of the boys scurrying down the fire escape. It must have been one of these boys who felt that Alf’s intervention was uncalled for. As Frank Penfold recalls: “The next morning, when everyone came to the Ojibway dock, there wasn’t a dock ring to be found. I don’t think anyone ever found out who did this. The rings were never recovered.”

Whether guests or islanders, young people found one another at the Ojibway Hotel – sometimes for the dances, sometimes for romance, or sometimes just to pass the time happily with one another on the dock or the hotel steps. Meanwhile, the older folks – the ones who weren’t fishing – played cards or snoozed on the veranda or sat, absorbed in newspapers, on wooden chairs beneath the hotel’s gaily coloured sun umbrellas.

One of the reasons for the particular success of the Ojibway Hotel was that it was able to combine the elegant with the casual. The two existed side by side on the dock. It was the place where men in jackets and ties and women in long dresses strolled after dinner, watching the sunset in the open beyond Empress and Fairwood islands. In one of the many pages of typed notes that Ruth McCuaig left in her files after she passed away, she wrote: “Until more casual forms of dress were adopted in the fifties…the men dressed up in white flannels, shirts, blazers and ties for dinner, while the women wore pretty summer pastel dresses or suits, silk stockings and heeled pumps, with a light sweater or shawl to be donned for the customary after-dinner stroll up and down the long wharf while viewing the sunset. The same garb would be worn by young men and their dates, who gathered at the hotel for the Saturday-night dances – the social event of the week. Quite a trick to keep those flannels spotless while priming the St. Lawrence engine and then turning the flywheel to start it, and coping with dew-laden seats in the boats for the journey back to the cottage.”

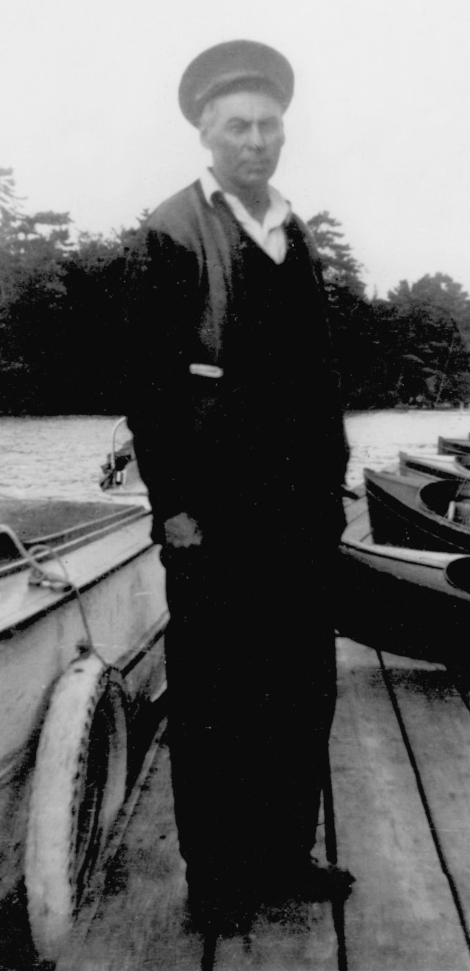

But the dock was also the Ojibway at its most casually, comfortably down-to-earth. It was the place where fishing guides were hired, where rowboats were clambered into. It was the place where Bert Bruckland, Hamilton Davis’s right-hand man, was consulted about almost everything under the sun.

For many, the proof that a summer holiday had truly begun was the first sight of Bert Bruckland’s familiar face. For 50 years, Bert was simply always there – chatting, overseeing, advising, warning, assisting. He had many duties at the Ojibway, but his hardware store (right) was the centre of his operations.

For 50 years, Bert Bruckland’s broad face was probably the image that most people associated with summers at the Ojibway. In the spring of 1906, Bert arrived at the Ojibway dock from Parry Sound on a barge that supplied the lumber for the hotel’s construction. He came from a family of sea captains and had been in the British navy. When he emigrated from England in the 1890s, he worked for his passage. His knowledge, his experience, his sense of humour and his efficient, practical manner must have impressed Hamilton Davis. Hamilton hired him on the spot.

For 50 years, Bert’s domain was the Ojibway dock. He made it his business to keep a weather eye open, encouraging islanders to head for home if the sky began to threaten. He would stand anxiously on the dock as guests’ and islanders’ boats approached during a storm. He took charge of boats, boathouses, repairs, the hardware shop, guides and general maintenance. Bert was also the postmaster. He was a true jack of all trades: a carpenter, a woodworker. He was even happy to turn a corner of his store into the local barbershop when required.

The dock was Bert’s, and among the things for which he was known was his intolerance of any “horseplay” on it. Running, pushing, playing children were often admonished by him and even, on occasion, saved by him. Ruth McCuaig tells of being a little girl on the crowded Ojibway dock and being knocked into the water between two boats. It was Bert – covering “many yards of wharf from the boathouse before any of the other adults realized what had happened” – who fished her out.

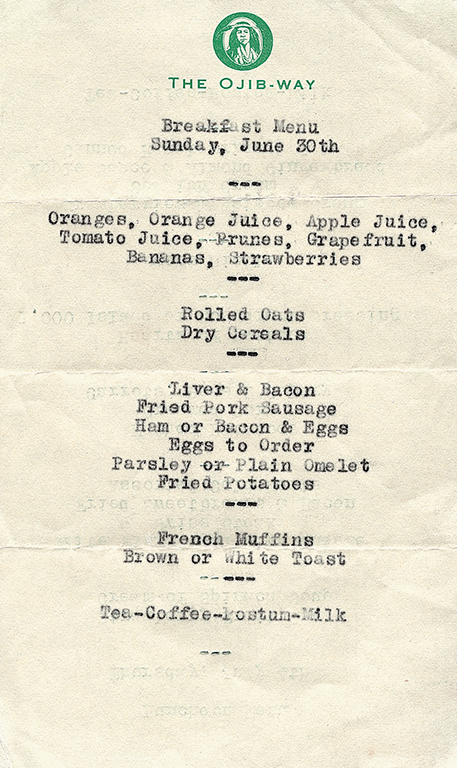

While birch-bark placemats and the Arrowmaker logo on these 1930 menus played up the dining room’s rustic, Native theme, the Ojibway’s fare was a little more international in scope. Guests enjoyed potatoes au gratin, Roquefort dressing and fried sweetbreads. But the hotel’s internationalism went only so far. Wine was decidedly unavailable.

Bert was also the overseer of guests’ luggage – an operation that he carried out with pride and naval efficiency. He made sure that the heavy trunks were unloaded carefully from arriving steamers onto the dock, sorted methodically and then transported on wheelbarrows by bellhops up to the hotel. Calm under fire, Bert once watched the arriving steamer Soo City suffer the indignity of crossed signals between engineer and captain, ploughing straight into the wharf at a considerable clip and pushing the dock well up onto the rocks. As the boat approached, Bert realized what was about to happen and had made sure everyone was out of harm’s way, but beyond that, nothing could be done except watch the impact and hear the crunching timber. Unruffled, Bert told the

captain that if he just kept going, he’d be able to do the bellhops a favour and deliver the trunks to the second floor himself.

There were other parts of the hotel that were important, of course, and guests were certainly fond of the dining room. Three solid meals a day were served there: a typical daily menu featured “rolled oats, ham and eggs, and French muffins” for breakfast; “whitefish baked with cheese” for lunch; and “pickled beef tongue or lake trout” for dinner. Waitresses, setting up for lunch almost as soon as they’d cleaned up from breakfast, sometimes got the impression that all the guests ever did was eat. The well-known actress Araby Lockhart, who worked as a waitress at the Ojibway in the late 1940s, said: “They want coffee. They want tea. I remember thinking people are just made to eat. That is what they do. They eat.”

Sometime in the 1920s, however, one of the guests did more than eat. Dr. Stephen Moffat Hay was enjoying his dinner when the waitress serving his table suddenly collapsed. She was carried into the Ojibway kitchen, where the doctor realized she was having an appendicitis attack. Using a butcher knife and the light of an oil lamp, he performed an emergency appendectomy.

But man shall not live by bread alone – so Hamilton Davis realized – and while the dining room was a crucial part of the hotel’s daily routine, the chapel services were fundamental to its weekly schedule. Two nearby churches had preceded the construction of the hotel. The first, a Methodist missionary church, was built on nearby Shawanaga Reserve, and the second, located just to the south of the Bellevue Hotel, served the small fishing village clustered in the vicinity of the lighthouse. It was in this small wooden church that Hamilton married Amelia “Millie” McIntosh in 1907. They spent their honeymoon in Ottawa. Millie died of cancer only nine years later and was buried in a cemetery in Medford, Ontario, on a hill overlooking Georgian Bay.

A year after Millie’s death, Hamilton married Louie Irene Cloke of Hamilton, Ontario. “Lou” was soon overseeing the housekeeping and kitchen staff, and would play piano in the lounge for the

guests. In June 1918, she gave birth to twin boys, Jeremy Griswold and Hamilton Cloke Davis. But the parents’ happiness was short lived. Both babies were born with diabetes, a fatal illness before the discovery of insulin. Young Hamilton Cloke died only 15 days after his birth and Jeremy succumbed to the disease at the age of five.

Sunday chapel was a part of Pointe au Baril summer life almost from the time the first cottages were built, and by the 1920s, regular services were held at the Ojibway Hotel. This would be appreciated by many of the hotel’s guests as well as cottagers, and so Davis embraced the idea. As well, a more low-key day of rest would provide a welcome respite for his staff and for his fishing guides from the busy demands of the rest of the week. Sunday chapel quickly became a tradition of the Ojibway Hotel.

Hamilton Davis married Amelia “Millie” MacIntosh (above right, seated in the centre, beside her mother, and showing her wedding ring) in 1907. In 1917, after Millie’s death, Hamilton married Irene “Lou” Cloke (above left, with their son, Jeremy). Millie MacIntosh was related, by marriage, to William Sing, the local realtor. Sing often held Sunday chapel services on the rocks in front of his cottage (left), where faithful attendees would bring their own pillows.

“In the shade of the pine trees on Ojibway Island,” the 1928 yearbook recorded, “a goodly company gather on Sunday afternoons in July and August, for the worship of God. These services were fostered in the earlier years by the earnest faithfulness of the late J. P. Rogers, the late Rev. S. H. Gray and others of like spirit. They are now carried on under the auspices of the Association and have become a permanent and welcome feature of the holiday life of the district.

Non-denominational chapel services were held every Sunday at the Ojibway. Usually outdoors, they were invariably well attended, and the favourite old hymns were sung with gusto.

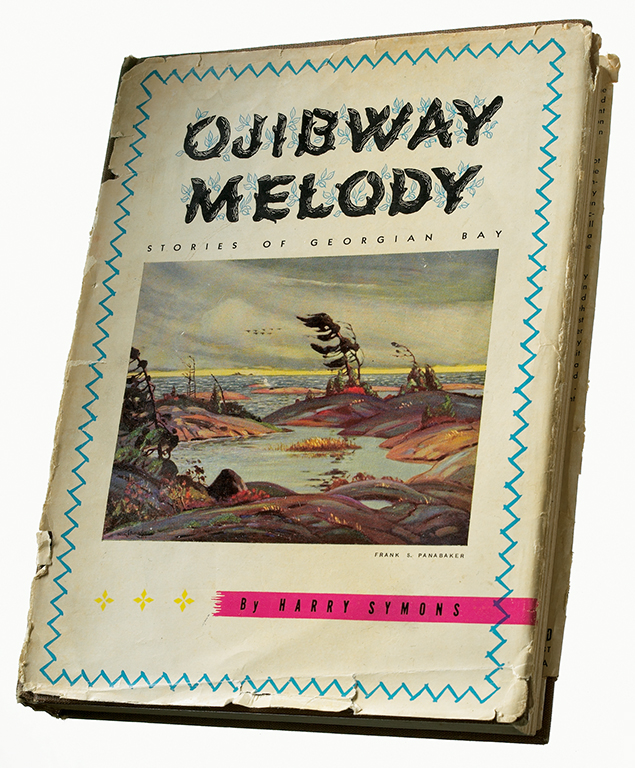

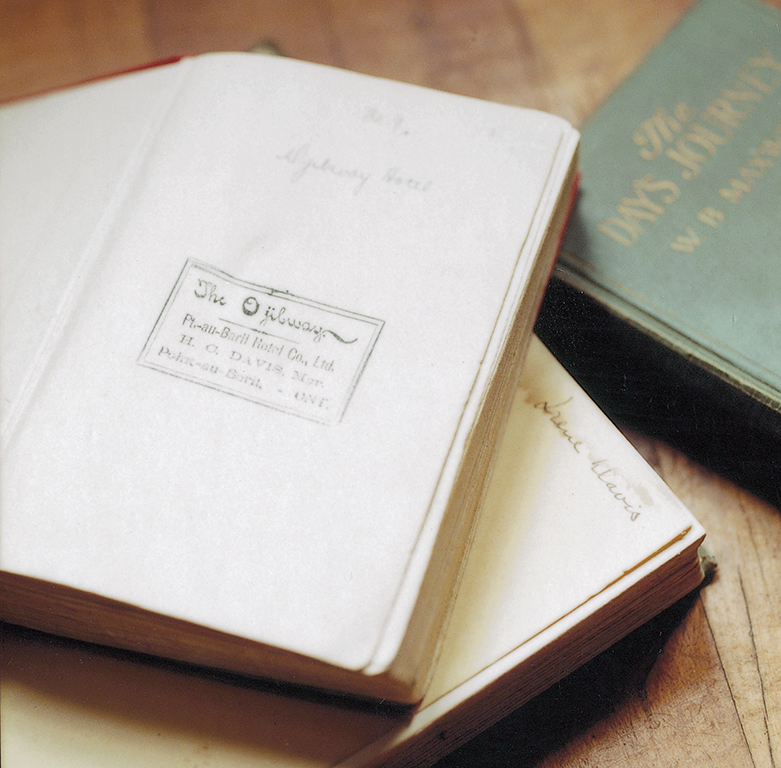

Harry Symons’s delightful memoir, Ojibway Melody, published in 1946, captures the spirit of old-fashioned Pointe au Baril summers. In 1947, it won the Stephen Leacock Prize for humour.

“The services are simple and direct, and are conducted by regular summer residents or visiting clergymen. The out-of-doors provides a setting of beauty and spaciousness and gives a sense of freedom to the worshipping heart. Men and women, tired in body and jaded in spirit, find healing and restoration in the fellowship of this hour, with its witness to the needs of the inner life and to the gracious power of the Unseen.”

But once Sunday was over, the hotel returned to more secular preoccupations. The veranda and the lounge were popular for bridge, for reading and for letter writing. There was shuffleboard just south of the tennis court. There was a three-hole putting course behind the dance pavilion, in the middle of the island. Later, a billiard table was placed in the games hall as well. It was popular with the older gentlemen guests, and if the occasional wager were made while the cues were being chalked, the Good Lord seemed well enough pleased with every Sunday’s fervent hymn singing to be much perturbed.

For those who were not fishing enthusiasts, the Ojibway’s veranda was the place to pass the tranquil hours of hotel life. Books were read there, letters were composed, diaries were kept up to date. There was a view of the water, cover from the sun and the rain, and on chilly days a fire was always crackling cheerfully in the big stone fireplace.

Miniature golf, tennis, shuffleboard and fishing were always available for guests. The less-active could relax with one of the books from the Ojibway’s library.

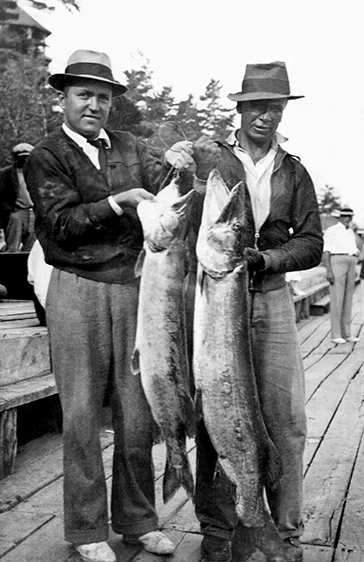

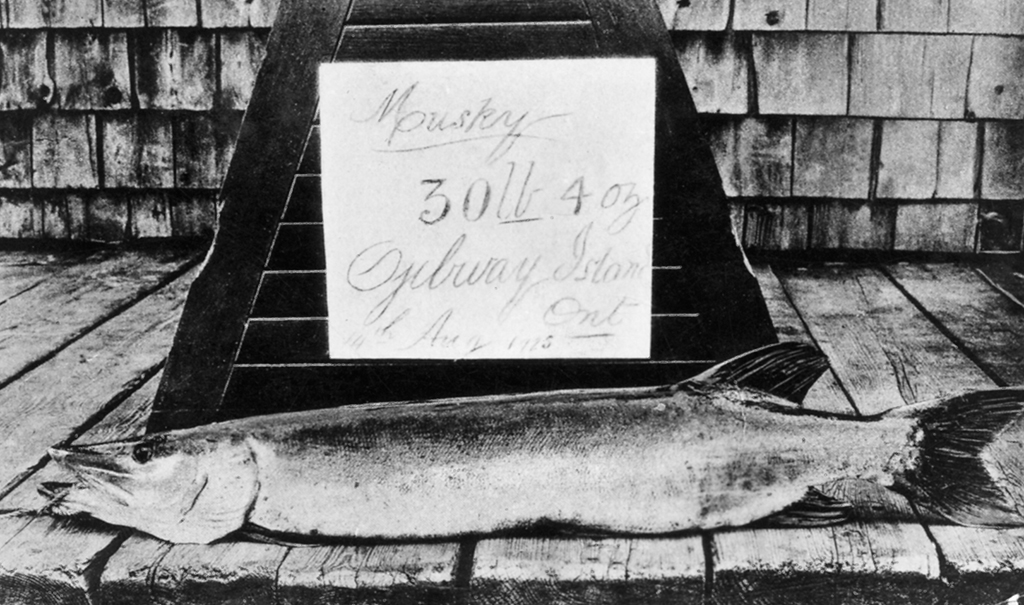

In Ojibway Melody, Harry Symons’s memoir of Pointe au Baril summer life in the 1930s, the author raises the question of the community’s “focal point.” “Architects,” Symons wrote, “talk with ardour and aplomb about the focal point of this or the focal point of that…. Something around which everything should, more or less, radiate and adjust itself.” Ojibway Melody is as meandering as it is charming – its focal point elusive – but eventually Symons gets around to answering his own question. Fishing, he contends, is the focal point of the summer life of Pointe au Baril.

In arguing his case, he points out that the area was “one of the spawning and breeding grounds of the bass and the ’lunge [and] the northern pike, the pickerel and the great lake trout itself. The selfsame Georgian Bay lake trout whose delicate filet you will pay a fabulous price for at the Plaza in New York City.”

And Symons was not exaggerating at all. In an advertisement that appeared in Harper’s magazine in 1908, the Grand Trunk Railway and the Northern Navigation System tempted sportsmen to Georgian Bay with a photograph of two pleased-looking fishermen holding a string of 26 hefty bass between them. The caption read: “The legal limit caught in 90 minutes.” Pointe au Baril was listed in the ad as one of the ports of call.

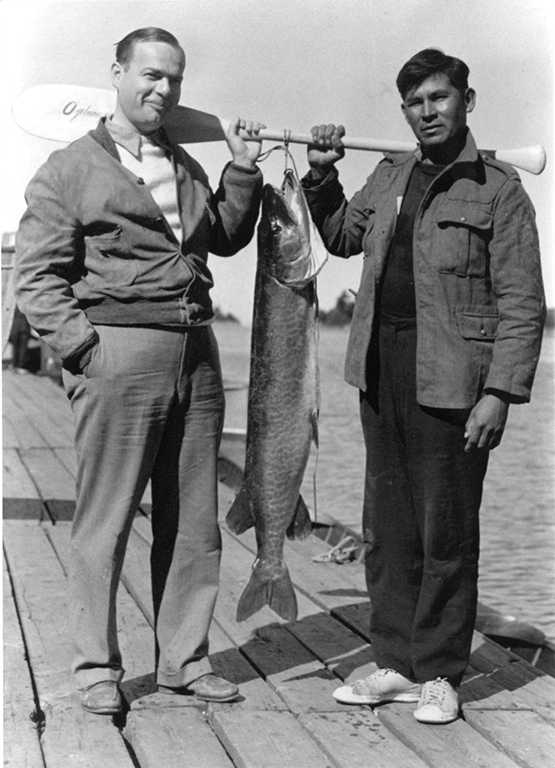

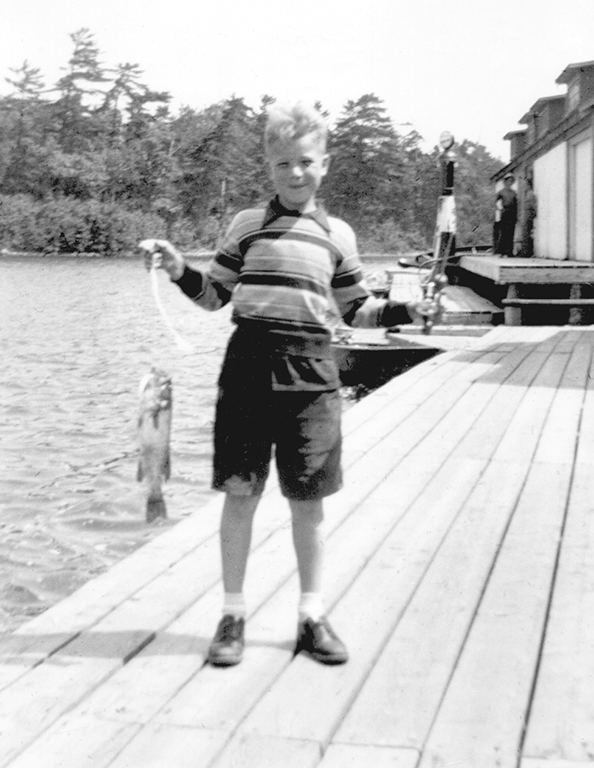

The fishing in Pointe au Baril is no longer what it was once. Pollution, overfishing, a steadily increasing tourist population, even the cormorants – all have been blamed for the decline. But there was a time when summer life in Pointe au Baril, and, indeed, day-to-day life at the Ojibway Hotel, did revolve around the rituals of fishing. And for the most part, the rituals of fishing revolved around the Ojibway dock. Bill Mosley remembers: “All the Indian guides used to sit along the dock in front of the grocery store.”

It was not uncommon for the guests of the Ojibway to spend every day of a vacation, except Sundays, on the water with a fishing guide, while those who preferred the non-fishing life read or played cards on the hotel’s comfortable veranda or strolled the Ojibway’s dock. Fishing prizes were coveted – a trophy for the week’s biggest catch sat proudly on the winner’s table in the dining room. Whatever fish were not eaten on shore lunches, or enjoyed at the tables of the Ojibway dining room, were filleted by hotel staff, packed in ice and shipped back to the homes of the triumphant fishermen.

The Ojibway’s celebrated Native Canadian and French Canadian fishing guides ensured that the hotel guests were satisfied with their catches. No one knew the area like the guides. They often worked with the same families year after year. Some clients and guides developed lasting friendships based on these annual outings.

Live bait, lures, rods, reels and line were always available at the Ojibway store for guests and islanders alike. But it was the guests who competed for the coveted hotel fishing trophies. They were presented with fanfare – for the biggest catch of the week and of the season.

Fishing arrangements were confirmed a day in advance with Bert Bruckland, who was in charge of the guides. In its busiest years, the hotel employed as many as 25 guides; at the eastern end of the Ojibway dock, a dozen fishing rowboats were pulled up at the end of the day. Bait was shipped to the Ojibway by train and steamer from Skinner’s in Toronto. Most men arrived at the hotel with a proud and abundant collection of tackle and gear, but lures, leaders, bobbers, sinkers, line and hooks could be purchased at Bert Bruckland’s hardware store on the dock.

Another fixture of the Ojibway dock was Albert Desmasdon. Born on a houseboat on Moon River, sometime around 1906, he worked as a young handyman for Bert Bruckland while still attending school.

Bright and capable, with an obvious knack for mechanics, Albert was noticed by Hamilton Davis, and it was Davis who arranged to send him to technical college in Hamilton for several winters.

The investment paid off – for both men. By 1923, Albert was working full-time at the hotel from spring to fall. In the winter, he cut the ice. It wasn’t long before he was in charge of the Ojibway’s boat shop, the hardware repair shop and all the maintenance tasks for the Ojibway. Guests, islanders, hotel staff – everybody knew that if something was broken, be it boat engine or water pump or generator, the odds were good that Albert Desmasdon would be able to fix it.

Mike Douglas, a longtime cottager, worked for Albert in the 1950s and remembers him as “a great teacher, a very smart guy.” He still recalls Albert’s words: “There are only three things that make a motor run – compression, spark and gas. And if one of those things is missing, the motor isn’t going to run.”

For many summers, Albert and his wife, Pearl, and their seven children lived in a small house on the south side of Ojibway Island. His full-time association with the Ojibway ended in the late 1960s when he and his sons opened Desmasdon’s Boat Works Limited in the Pointe au Baril Station.

On Ojibway fishing expeditions, rowboats were often towed behind the hotel’s launch. Once at the chosen destination, guests could row on their own among the islands to catch their daily limit. A highlight of the outings was the shore lunch, prepared for guests by the guides.

The rocks and shoals of Georgian Bay ensured that Albert Desmasdon (above, between two bellhops, and at work, below) was always busy repairing engines and replacing broken propellers.

Albert was also a good driver. He drove Hamilton Davis to his winter retreat in Florida every year – once with near-catastrophic results.

“My dad had never looked at a golf club in his life,” Joe Desmasdon remembers with a chuckle. “But they stopped in Georgia one year, and Mr. Davis talked him into going for a round of golf. And out on the course, Mr. Davis was telling Dad what to do. Sort of showing him how to play. Well, I guess Dad was a pretty strong, fairly athletic guy, and I guess he really lucked out because he happened to beat Mr. Davis. And he used to say that Mr. Davis didn’t talk to him for the rest of the trip – all the way to Florida.”

This was exactly the kind of story that Harry Symons loved. Ojibway Melody has the pleasant, relaxed tone of someone writing to amuse himself, and nothing amused Harry more than poking fun at things and people who, in actual fact, he held very dear. Symons was a genial Toronto businessman who bought the island called Yoctangee in 1935. His description of the opening and closing of a Pointe au Baril summer place could only be written by someone who had dealt with bats and mice and smoking fireplaces and lost keys many times. His chapter on Will Oldfield’s commercial fishing operation – the Oldfield family, one of the earliest settlers of the area, ran a store and a fishing station at Double Island as well as the Bellevue Hotel – displayed a journalist’s curiosity and eye for detail.

Yoctangee was where Harry Symons wrote Ojibway Melody. In 1952, when he sold the cottage, he wrote to the new owners: “When no-one is looking, please kiss Yoctangee for me and tell her that she is still my first love.”

But Symons never gave the impression of taking his literary aspirations too seriously. The theme that runs through almost every page of Ojibway Melody is his affection for Pointe au Baril and for the hotel that stood at its centre.

Certainly the dock’s activity caught Harry Symons’s attention. “As you stroll along the lengthy dock in the warm summer sun,” wrote Symons during one of those industrious afternoons when he was writing Ojibway Melody at his cottage on Yoctangee in 1944 and 1945, “perhaps you may meet the Mathews, or Harry Gordon…. Maybe it’s Unc McCuaig with an enviable string of bass, or Roy Warren with his briefcase, of all things, or one of the joyous Rogers group, or the Jacobs, Goulds, Reynolds, or Violet MacKenzie…or Southams from Flat Rock, down Hemlock Channel way, or Tom Fairlie, whose island, Fairwood, is a showplace of natural scenic beauty combined with human ingenuity. Or Trevor Temple and his wife, Audrey, who are proud grandparents now, or Timber Mulqueen just in from Kish-Ka-Dena that lies like a jewel out amongst the far-flung shoals. Or the Rogans, of whom Johnny is not the least famous, or grave, kindly Doctor Hill, or one of those old-timers, the MacIntoshes, the Camerons, the Kelsos, the Garbers or the Merchants. Or from Nares Inlet to the north, the O’Briens, the Lightbournes or the Phillip Ketchums…sauntering happily along, whiling the golden hours away in pleasantry and companionship. Garbed in whatever their immediate fancy may dictate. Sunburnt, laughing, exchanging courtesies and idle banter, or serious consultation on fishing, hunting, sailing or swimming.”

But perhaps Symons’s best tale – certainly, his funniest – could well have been written by Stephen Leacock. (In 1947, the first Stephen Leacock Award for humour was given to Harry Symons for Ojibway Melody.) It is his description of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Howson, an older couple from Cincinnati who first bought Yoctangee in 1903 and from whom Symons later bought his beloved island.

It was the place to swim, to dive and to frolic in the never-too-warm water of Georgian Bay. It was also the place to gather after breakfast for an outing in one of the hotel’s launches. For the hotel guests, met on arrival, serenaded on departure, summer holidays began and ended on the Ojibway dock.

The scene Symons describes, we may guess, took place in the 1920s, as the Howsons were leaving the dock of the Ojibway Hotel in their newfangled outboard. It was customary for islanders to visit the hotel almost daily. The Howsons were regular fixtures. Symons informs us dryly that Mrs. Howson “liked to talk a lot more than Arthur did” and that she usually sat afore, facing the bow while he operated the motor in the stern.

“They’d gotten their mail and the boat had drifted just a little way from the dock while Arthur tugged, and jerked, and fussed and twiddled. During all these operations, Mrs. Howson went right on talking. As so often happens, all of a sudden the contraption went off with a bang and away the boat flew. But not with Arthur Howson aboard. Not with Pop Howson in it. My, no! No, indeed. For, caught momentarily off balance, Arthur shot headfirst over the stern and entered the water, still in complete silence. But not so with Mrs. Howson. Quite unaware that old Pop had left her, she ran tranquilly and pleasantly on. The folks on the dock swore they could hear her quite clearly. She was berating Arthur in her gentle way for failing to do something he should have done, it seemed. They say it made a very unusual picture. What with old Pop floundering around in his clothes just off the dock a little, and the boat circling in quite a large circle of its own accord, around and around, and Mrs. Howson quite innocently chattering away to an Arthur purely imaginary.”

After reading one of Harry Symons’s stories, we are left to stand on the same dock, to pace back and forth along its generous expanse, and to try to imagine what the Ojibway looked like when, in the lustrous summer evenings, well-dressed couples strolled at the ritual of sunset. The unchanging summers in Harry Symons’s Ojibway Melody were fading away even as he wrote them down. Nobody guessed that the things he took such delight in observing on the dock of the Ojibway Hotel were soon to become the scenes of a bygone age.

Everything revolved around fishing.

Hook, Line & Sinker –

If there was a single activity that was fundamental to life at the Ojibway Hotel, it was, without doubt, fishing. “The bays and channels are full of black bass, pike, pickerel, and the famous fighting warrior, the Muskalonge [sic]” – boasted an early brochure. At its height, the hotel hired as many as 25 guides a day, owned a fleet of rowboats and employed full-time fish cleaners to attend to the guests’ daily catches. But the success of the Ojibway Hotel may have been based on something more ingenious than good fishing. It may be that Hamilton Davis provided many couples with their perfect holiday. The men could head off for the day in a rowboat with their guide, their gear, their live bait from Skinner’s, their shore lunch, and the women, pleased to be rid of them for a while, could get happily on with other things.

“Imagine the breathless thrill of a savagely smashing, plunging giant fish – Ojibway’s waters teem with’em.” ”

~

continue to { Chapter 4 }