“While in Muskoka there is room for thousands of visitors, there is room for millions in Georgian Bay.””

The Ojibway is an old place, not as far away from everything as it used to be. It’s on an island, just inside the outer shoals of the eastern edge of Georgian Bay. It used to be a long way off but is not so difficult to get to now. A few hours on a highway, a few minutes in a boat. And there it is.

After the hotel’s second expansion, in 1913, life in the lounge remained unchanged for decades.

It’s as if the stone stairs and the gracious veranda remind anyone who approaches that time slips away, but that not everything slips away with it. Some things we hold on to. Summers are faster and noisier now than they were when Hamilton C. Davis first set eyes on the 42-acre island where he would build his hotel. But some things we manage to preserve. The weathered shingles, the expansive dock, the stately tower and the shafts of white pine are familiar enough sights to people who spend their summers in Pointe au Baril, Ontario. But the Ojibway is the kind of place that looks familiar even to people who have never seen it before. The creation of a courtly former railway agent from Rochester, New York, it was built in 1906 and seemed, even in the earliest days, to embody summers past.

There are snapshots. There are family traditions. There are recollections of a dock on a carefree afternoon, of crackling wood in an old stone fireplace when the weather turns, of the slowly deepening colours of a sunset. We remember the songs we used to sing at campfires, or the swimming spots we knew, or the endless dusks we played in when there was no school the next day.

The Ojibway makes people think of their summers because it has the look of a memory held close to heart. It’s the kind of place that has often been allowed to disappear. Its survival is miraculous, really, and now it stands – modestly enough, comfortably enough, graciously enough – as witness to what has gone and to what, like a faded regatta ribbon, has been saved from the passage of time.

Between the summer of 1906, when it opened as a hotel, and the summer 60 years later, when it stopped taking overnight guests, the Ojibway had its ups and downs. On the whole, its ups were long running – “comfortable furnishings, diligent service and a cuisine of the very highest standards” was the opinion of a travel writer in 1933 – and its downs were less catastrophic than those suffered by many of the grand hotels that once dotted the Muskoka region and the islands of Georgian Bay. The Ojibway never burned to the ground. It never went bankrupt. It underwent a minimum of the ill-advised “improvements” that were made in the name of modernization. It had its rough years – “poor iron beds, tepid water and very noisy at night,” wrote one disappointed cottager after she dropped her mother off for a stay near the end of the Ojibway’s hotel years – but it never fell irredeemably into disrepair.

Today it is no longer a hotel. It is a club operated as a social and recreational centre for Pointe au Baril’s summer community, but the Ojibway holds close to the claim made decades ago in one of the hotel’s brochures. The island remains “the centre of a group of other islands forming a summer colony of…families of the United States and Canada.” And the Ojibway’s front dock is still “the community’s Main Street.”

The place is a palimpsest of sorts: “a manuscript written over a partly erased older manuscript in such a way that the old words can be read beneath the new.” For there, etched beneath any vivid blue day of the Ojibway’s present, is its past.

Bert Bruckland ruled the dock with a firm, genial hand. He was, for many, the personification of an Ojibway summer.

The hotel’s launch, the Royaleze took guests for stylish excursions.

At the hotel’s gift shop and store “every requisite may be purchased.”

Look, there’s old Bert Bruckland, in his white captain’s hat and khakis, telling the kids to stop their horseplay on the dock. He started at the Ojibway the year it opened and retired 50 summers later, and he has fished more than a few children out of the drink over the years. And there’s Albert Desmasdon wiping the grease from his hands after working on the hotel’s launch, the Royaleze. And there’s the French Canadian fishing guide everyone always wanted, Napoleon Longlade, helping a portly guest into one of the Ojibway’s rowboats for an outing to some secret spot where the black bass will be biting for sure. And there, on the path, beside the laundry, is young Emmaline Black talking shyly to Carl Madigan, the handsome lighthouse keeper. And there, on the dock, lighting his pipe – that’s the genial author Harry Symons chatting with the local historian, Ruth McCuaig. And overseeing all this, standing at the top of the stone stairs in his shirt and tie, woollen sports jacket and tweed cap, gaunt and thin as a rake, is Hamilton Davis.

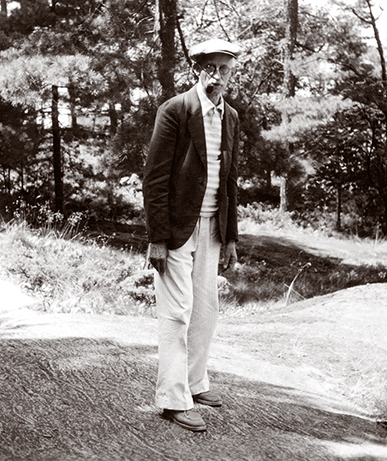

Hamilton C. Davis, the founder of the Ojibway Hotel, was an unmistakable figure in Pointe au Baril summer life. He was, says cottager Tom Symons, “a gentleman in his comportment, his values, his way of treating people. That became the hallmark of the Ojibway.”

Hamilton first came to Pointe au Baril in 1903, the year after his sister Helen Davis had visited, fallen in love with the place and – for $5 – bought an island. Hamilton was no less struck with Pointe au Baril’s beauty. Those who know Georgian Bay’s archipelago can imagine what he must have felt when he first saw the maze of islands and channels and bays that Helen had described to him so enthusiastically.

Of course, Georgian Bay is not everyone’s cup of tea. “Lawrence, you told me this was the most beautiful place in the world,” wailed the little woman with the dog. “It is,” he tossed over his shoulder at her, “but it takes some getting used to.” This exchange, taken from Katherine Govier’s novel Angel Walk, captures the gulf that often exists between those who love Georgian Bay and those who stand, bewildered and irritated, on a bare rock, in a brisk wind, cautious of rattlesnakes, bothered by horseflies, surprised by the all-too-invigorating temperature of the water, looking over a landscape that appears to them to be harsh and austere and unwelcoming.

While some hotel guests were content to stay on Ojibway Island, others, often in the company of nearby cottagers, were more adventurous. The kitchen staff packed luncheon hampers for guests who wanted to bask on sheltered rocks or explore the wilder, outer side of Georgian Bay.

The eastern shoulder of Georgian Bay, as described by Claire Elizabeth Campbell in Shaped by the West Wind, is the “least hospitable of the four shores.” Scraped smooth as bone by the advances and retreats of glaciers more than 10,000 years ago, “the gneiss bedrock is home to scrubby vegetation such as juniper, white pine, red oak and cedar, but the acidic, shallow, poorly drained soils could never support the mixed agriculture and density of settlement found on the south or west shores.”

Campbell’s seemingly negative description is actually quite the opposite, and people who love Georgian Bay have made this kind of counter-intuition something of a trademark. That the water is cold, that the weather can get a little strenuous, that there are bats behind the shutters every spring, and that there are sometimes fox snakes on the path to the outhouse – these are often the reasons real Georgian Bayers give for liking Georgian Bay.

Campbell’s book, for the most part, is a celebration of the history and stark beauty of a region that was described in a 1933 edition of the Literary Digest as “a paradise” of “winding, forest-bordered channels and intriguing bays.” Campbell makes it clear that one man’s “scrubby vegetation” is another man’s wind-bent pine; that a landscape some see as barren and cold and hostile is to others “the perfect balance of water, land and sky,” as Tom Lawson, a long-time Georgian Bay cottager, once put it.

“I watch the sunlight break over the waves, and the waves break over the shoals.” ”

Apparently, Hamilton Davis saw the beauty of the place at once. But that was not all that attracted him. He was also an entrepreneur. At the age of 38, he was between things, trying to find a commercial niche that would suit his considerable but, so far, unaligned talents, and he was struck with the area’s business opportunities. Here were prospects.

It was clear to Hamilton that railway lines were going to continue to be built northward. Economic expansion was pushing them in that direction. But so was a new kind of tourism: a spirit of adventure that would come to be locally exemplified by a schoolteacher from Missouri.

In the early years of the 20th century, Lucy Young taught second grade, and once she had a class that tried her patience almost beyond endurance. So difficult were her students and so worn down was Miss Young by the end of June, that on the first day of her long-awaited summer vacation, she marched into Union Station in St. Louis and asked for something no more specific than a ticket to “someplace far, far away.” Lucy bent over a map and a railway schedule with an accommodating train agent, and together they selected a destination that appeared to be about as far north as it was possible to get. Less than a week later, Lucy Young was in Pointe au Baril.

The idea of “getting away” was relatively new to a culture that had so recently been concerned with the pioneering business of “getting to,” but it was an idea that was taking hold. Hamilton Davis had sold enough train tickets in his days as a railway agent to know that the energetic and educated members of the North American middle class had the money to travel. Their vacations would be shorter and more modest than the grand European tours of the wealthy, but their numbers were greater. The question was: In a continent that had no ancient castles, no crumbling villas and no stately ruins to visit, where were they going to go?

They would come here, so Hamilton must have concluded during the two or three summers when he explored the islands of Pointe au Baril in his little gaff-rigged skiff and hatched the plan that eventually became the Ojibway Hotel.

It was the simplicity of Pointe au Baril summer life that appealed to so many, and in this the hotel was perfectly in synch with the islanders. Nothing much more was necessary than a porch with a view, a rowboat or canoe, and some cool water to paddle your feet in when the day got warm.

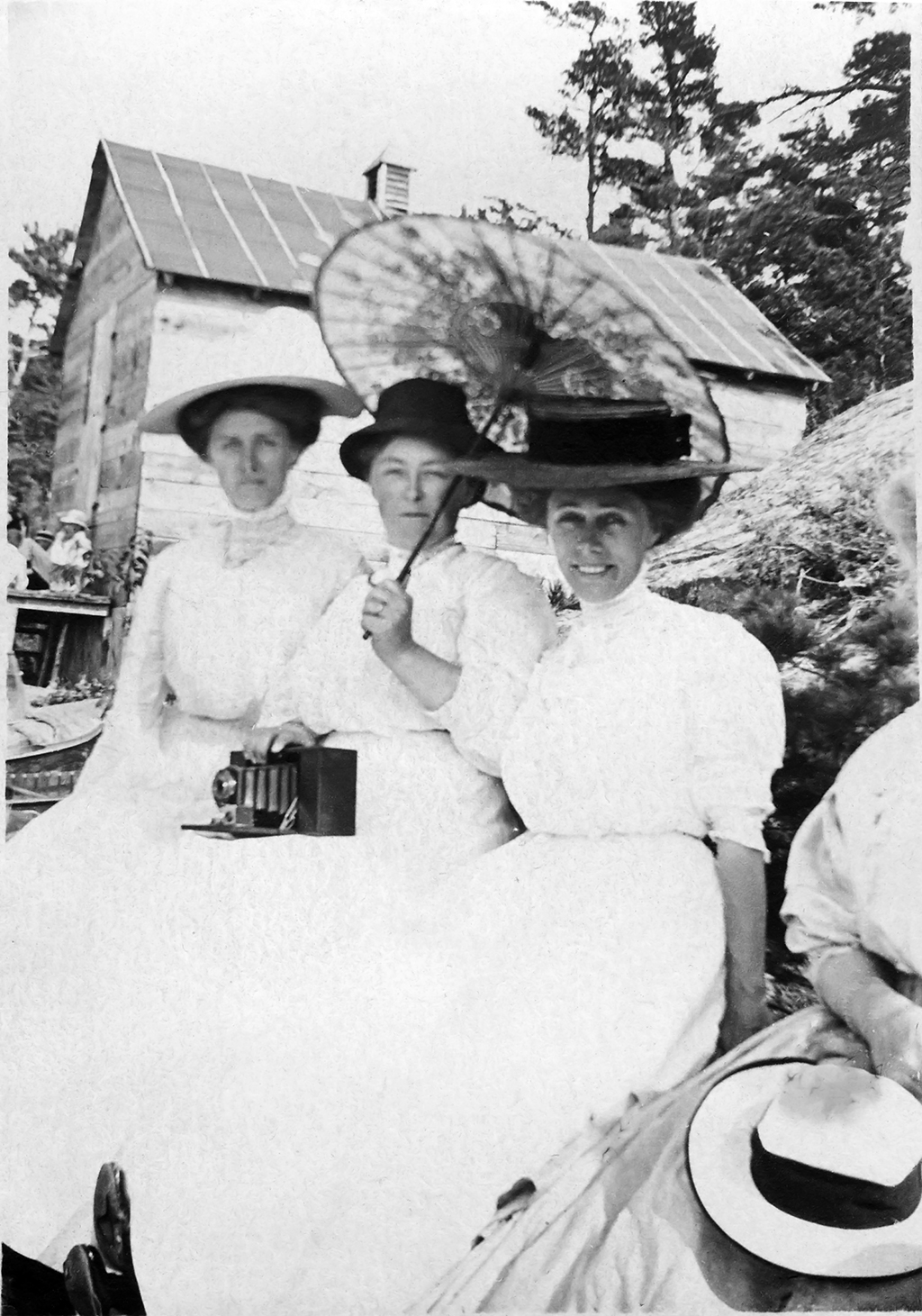

He was sometimes in the company of one of his three sisters. They were bright, confident, accomplished women. Helen would become an executive director of the YWCA, and Katharine, a noted reformer and suffragette, would be appointed superintendent of the New York State Reformatory for Women. The year after Helen’s first visit, Katharine had come to Pointe au Baril and had purchased her own island. A Rochester couple, the Moshers, had come with Helen on her first visit, and they too were now among the first Pointe au Baril islanders. The Howsons, from Ohio, were also building a cottage, one they would call Yoctangee.

He was sometimes joined on his outings by May Bragdon, a family friend from Rochester who, judging from her diaries, had a serious crush on Hamilton. May would also end up buying an island. A spirited, intellectually ambitious young woman, she was the sister of the well-known Rochester architect and theatre designer Claude Bragdon. Like the Davis sisters, May quickly developed a passion for Georgian Bay and for the summer community of Pointe au Baril.

Hamilton Davis had faith in the judgment of his friends and family. He knew that they were neither eccentric nor exclusive in their tastes. It must have seemed likely to him as he looked for a suitable site and contemplated the marketability of his plans that enthusiasm for this corner of the world would be shared by many.

Certainly, the signs were there that he was on the right track. Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, a treatise published in 1854 about living simply in nature, had become a popular and influential book by the early 20th century. “Most of the luxuries, and many of the so-called comforts of life, are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind.” This could well have been the motto of many of Georgian Bay’s early summer residents.

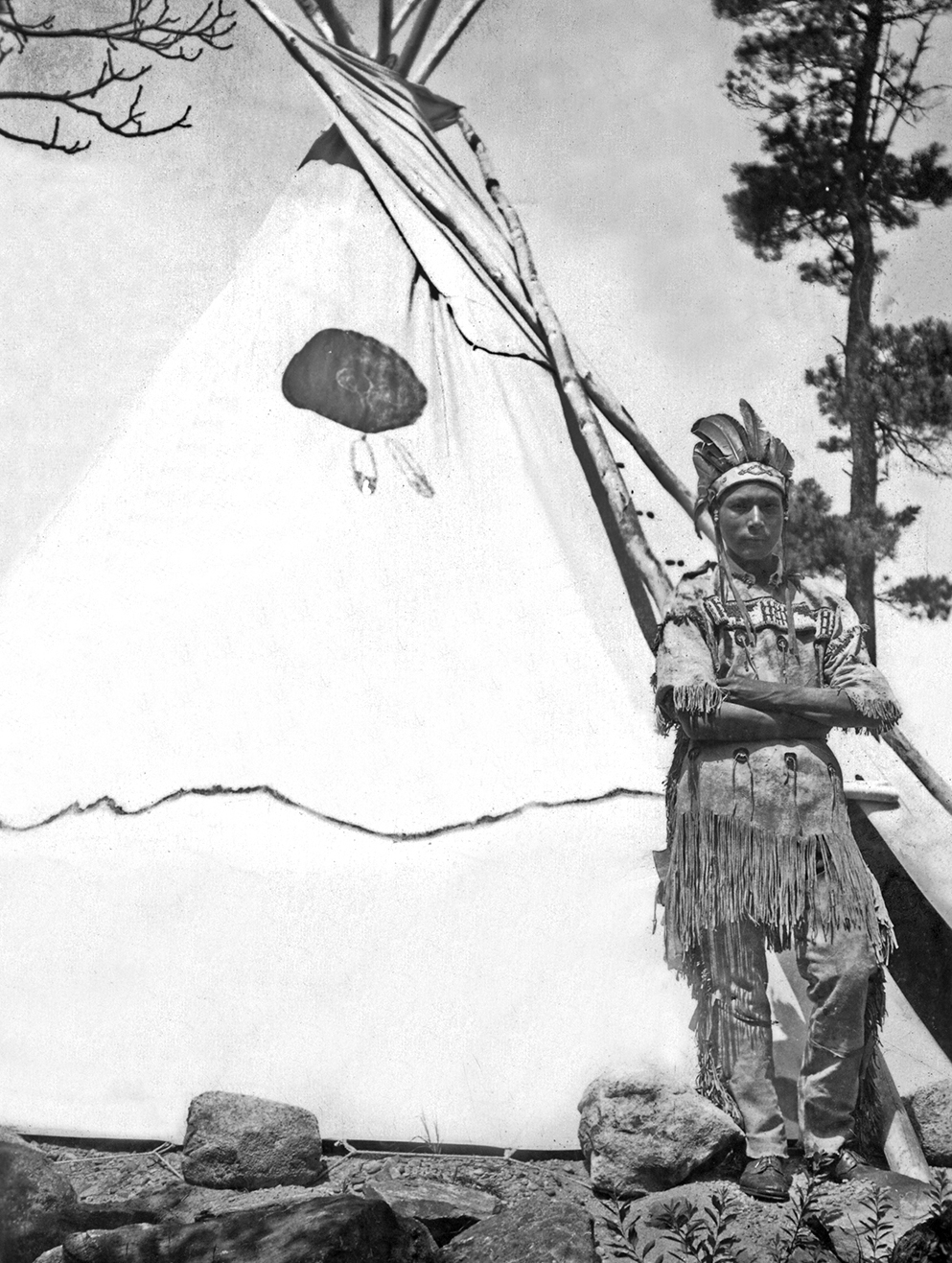

So well known was Longfellow’s Hiawatha, there were guests who imagined meeting the Ojibway warrior – or someone much like him. Calvin Nogonosh was hired in the 1930s to greet visitors in front of a teepee beside the hotel. Quill baskets, created by Ojibway women and based on traditional designs, were popular items in the hotel’s gift shop.

A year later, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published The Song of Hiawatha. This epic poem, which described the efforts of a young Ojibway to preserve his people’s way of life, was an enormous success in the United States. It spawned an enthusiastic, if not always well-informed, interest in Native culture. Hamilton Davis knew that by enlisting the help of local Ojibway fishing guides, and even perhaps by naming his hotel the Ojibway, he could capture the imaginations of those who might venture so far to the north. For the hotel’s logo, Davis used a 1902 postcard image of Arrowmaker, the father of Minnehaha, the young maiden Hiawatha married.

The wilderness, once considered something to be defeated and tamed, was becoming, in the popular imagination, a place of recreational and spiritual possibility. Now that the risk of being killed or injured by the great outdoors was not what it once had been, nature and the fresh air that blew through it were seen to be uplifting and salubrious. Canoe clubs and hiking groups were flourishing throughout the northeastern United States and central Canada; the camping movement was gaining momentum. The idea of a holiday that was bracing, picturesque and rustic was very much in fashion.

“There is a lightness out on the water, a sense of possibility untethered by earthbound expectations.””

The Bellevue Hotel was a plain three-storey structure just across the main channel from the Pointe au Baril lighthouse. It had opened in 1900 and was usually full during the summer season. Mazo de la Roche, the Canadian-born author of Jalna, stayed there for two summers. Once, she shocked her fellow guests by going out in a rowboat unchaperoned – with a man. “It was glorious to skim between the islands, with the sunset blazing red behind us and the pine trees, black as thunder, on either side,” she wrote in her autobiography, Ringing the Changes. “The channels between the islands were narrow, the air so clear that every frond, every mossy ledge of rock was reflected with exquisite accuracy in the water.”

In 1903 Hamilton Davis oversaw the construction of his sister’s cottage on St. Helena and that of another friend from Rochester on a nearby island called Oneishta. By 1904 he had purchased an island of his own. He named it Iroquois, and it appears that for a year or two, he worked as a contractor in the area.

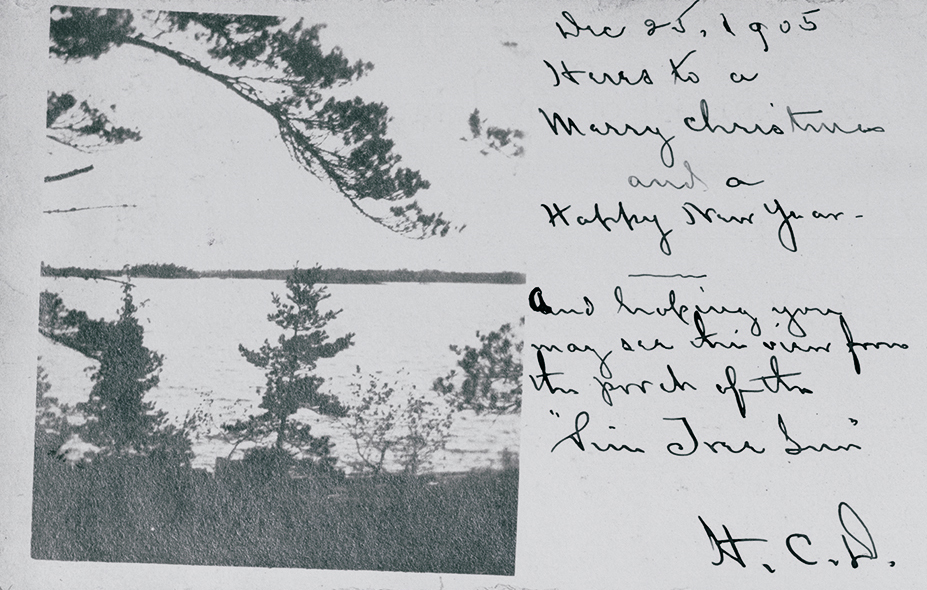

Originally calling the hotel “Pine Tree Inn,” the winter before it opened, Hamilton Davis sent a postcard (above) to May Bragdon. Hotel guests, islanders and their servants congregate at the front of the newly opened – and newly named – Ojibway Hotel.

Hamilton Davis became friends with the genial Jack McIntosh, affectionately known as the Mayor of Pointe au Baril. The McIntosh family ran a commercial fishing and fish-packing operation, a general store and a bed-and-breakfast, all of which were located near the Pointe au Baril lighthouse, and it seems likely that Hamilton used Jack as a sounding board as he formulated his plans. Twice, in the years between 1903 and 1906, Jack made winter visits to the Davis family home in Rochester, although it may have been the sparkling personality of Helen and not the aspirations of his friend, the would-be hotelier, that drew him there. In any event, by 1904 Hamilton Davis had made up his mind. He knew what he was going to do.

Committing his own savings, he convinced friends and family to invest in his plan. John A. Graham, cashier; Samuel B. Griswold, railway passenger agent; and William DeGraff and Herbert J. Stull, attorneys-at-law – all Rochester-based – were the first directors of the Pointe au Baril Hotel Company Limited. The capital raised was $15,000.

Helen Davis (left), the younger sister of Hamilton, first came to Pointe au Baril in 1902. She remained a cottager for the rest of her life. Hamilton paid $210 for the 42-acre Ojibway Island, at $5 an acre. One of the island’s many assets was the deep water, which accommodated large steamers.

The Ojibway Hotel opened on June 23, 1906, and it was an immediate success. The hotel’s guests were middle- and upper-middle-class folk who arrived with their trunks, their long dresses, their linen suits and their summer hats. They came for two-, three- or four-week stays by train from Rochester, from Cleveland, from Cincinnati, from Pittsburgh, from Buffalo, from Hamilton and from Toronto. They were travellers who disembarked from the steamers that brought them from Collingwood or Penetang or Parry Sound. They came to relax on the hotel’s pleasant veranda, to stroll the hotel’s dock at sunset, to play bridge, to read, to row, to paddle, to swim and, of course, to fish.

Whether it was while sailing races were getting underway, steamers were landing, the regatta was being organized, or fishing guides were meeting their customers, the Ojibway dock was the centre of activity.

The Ojibway Hotel was neither particularly grand nor particularly luxurious. No one expected it to be. It was clean. It was well run. It was quaint. Native and French Canadian guides rowed guests out to catch black bass, pike and muskellunge, and then, landing at a sunny point or sheltered cove, cooked up a shore lunch of fish, potatoes and baked beans. In the hotel’s dining room, a pretty Ojibway girl drifted silently from table to table in beaded buckskin and moccasins, filling water goblets. No doubt there was a copy of The Song of Hiawatha on the hotel’s bookshelves.

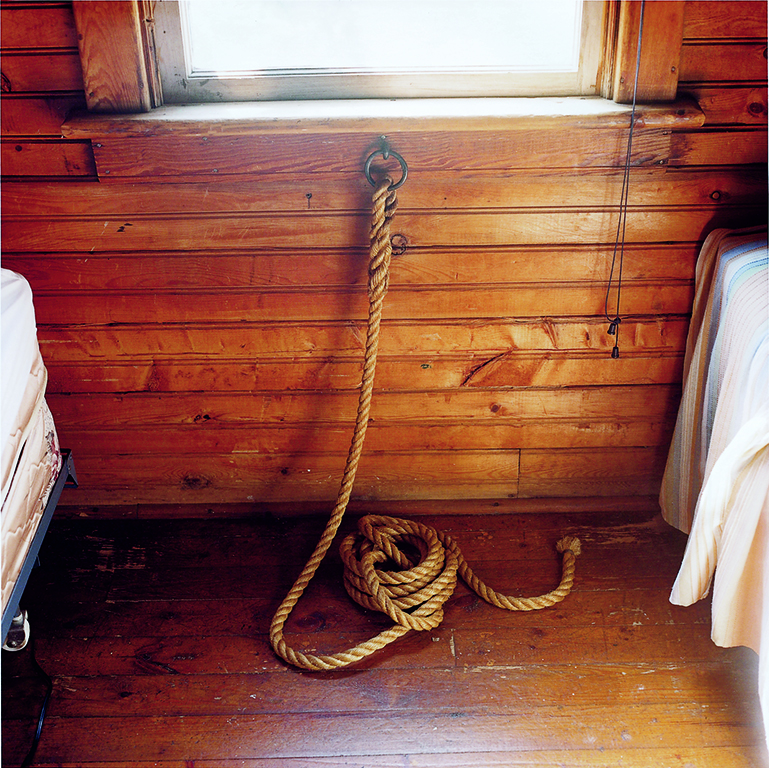

The Ojibway’s simplicity created the illusion of roughing it without anyone ever having to do so, and its rustic appearance was an important part of its appeal. The dining room was unfussy. The veranda was not sumptuous. The bedrooms were plain and functional. The fire escapes were coils of rope neatly looped by the windows on the second and third floors.

In contrast to an age when even the most humdrum hotel feels the need to leave wafers of chocolate on the pillows of turned-down beds, the Ojibway made no apology for not being fancy. In fact, it boasted about its lack of pretension. As an early brochure put it, “The Ojibway provides homelike living conditions for those who wish to enjoy the rugged beauty and bracing air of Georgian Bay, either in relaxation or in enjoyment of summer sports.”

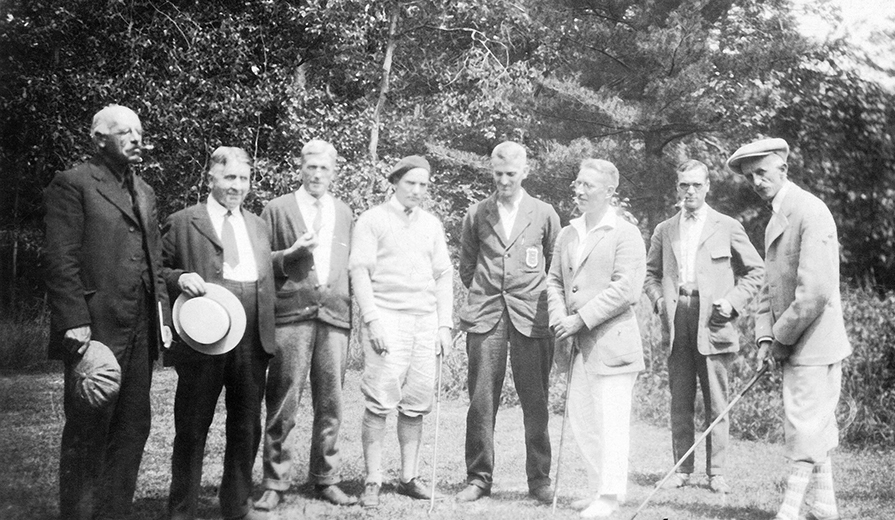

Hamilton Davis (above, at right) and the executives of the Pointe au Baril Islanders’ Association shared responsibilites running the Ojibway, such as religious services, fire protection, channel markers, hiring a physician and organizing the annual regatta (above, right) – an event that continues to this day.

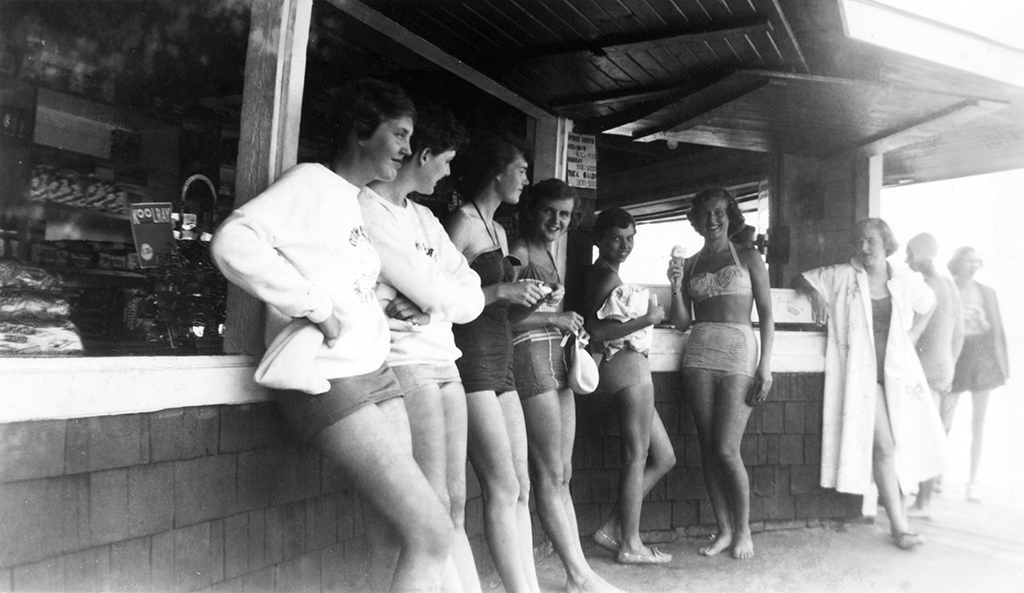

As well, the Ojibway became, almost immediately, central to the growing population of cottagers of Pointe au Baril. The first islanders’ regatta was held at the Ojibway dock in 1907, and is still held there, on the first weekend of every August. The Pointe au Baril Islanders’ Association was formed at a meeting at the Ojibway Hotel in 1908, and for many years Hamilton Davis was listed as either the secretary or the treasurer of its executive. It was almost a daily ritual for many cottagers to make the trip to the Ojibway to meet the steamer that brought the mail and to buy provisions at the store. Later, visits to the gift shop, pickups from the laundry and Saturday-night dances all became part of a week’s routine for many cottagers. Its dock quickly became the natural place for boys to look for girls and, by happy coincidence, for girls to pretend that they were not looking for boys.

The histories of the Pointe au Baril cottagers and the Ojibway Hotel are so entwined it is difficult to follow the thread of one without becoming tangled in the other. More than a few guests, introduced to Pointe au Baril through a stay at the hotel, ended up buying property in the area and becoming cottagers. And more than a few islanders – perhaps while opening up, perhaps while escaping cottage repairs, perhaps while weathering a marital three-day blow – were the Ojibway’s occasional guests.

Indeed, so successful was Hamilton Davis in making the Ojibway a place that most cottagers thought of as theirs that when he decided to sell the business, after running it for 36 years, it was a group of islanders who stepped forward to buy it. It was unlikely that they would ever turn a profit. There were wiser investments in 1942 than a big old hotel on Georgian Bay. Their intention was to ensure that the Ojibway continue as a suitable and essential part of the summer community of Pointe au Baril. They’d be pleased with the dividends.

The property has never been more energetically occupied than it is now: the tennis courts are busy; the fitness and Pilates classes are well attended; the art classes are fully subscribed; the children’s day camp is a success; the dock is busier than it ever was in the hotel’s heyday. The Ojibway is far from being a museum. And yet it is somehow impossible to walk around its grounds or sit on its veranda without contemplating its past.

“Ice cream wasn’t the only reason that boys visited the Ojibway dock on a sunny afternoon”

Hamilton Davis envisioned a place that was a centre for islanders as well as for guests. He encouraged cottagers to use the Ojibway’s facilities, and the tradition continues: islanders’ boats have always been welcome at the Ojibway dock.

It is often imagined that the look of the Ojibway, like the look of many of the old cottages in the area, is simply the way things were naturally built whenever construction took place near glacier-smoothed rock, whitecapped water, rustling birch trees and wind-bent pines. It may be a little disconcerting to learn that, even in 1906, it was a little more self-conscious than that.

In 2001, ERA Architects of Toronto, commissioned to study the architectural heritage of the hotel, reported that “the Ojibway was a direct descendant of the Great Camp Movement initiated by wealthy Americans who built rustic retreats in the Adirondacks.” And then, as if to silence any stubborn claims to regional originality, the same report quotes the definition of a well-established style – “Rustic Work” – from a 19th century architectural dictionary: “decoration by means of rough woodwork, the bark being left in place, or by means of uncut stone…will cause the general appearance of what is thought rural in character.”

The Ojibway Hotel’s bark-covered columns, twig furniture and birch-branch banisters – the handiwork of local craftsman George Izzard – were already pointing to the past on the day the first guests were greeted on the dock by the hotel’s proud manager. But whether or not such a past had ever really existed was beside the point, as far as Hamilton Davis was concerned. He understood that the Ojibway Hotel was not the kind of place that anyone wanted to think of as new, even when it was. The traditions that became part of life at the Ojibway – the shore lunches, the veranda teas, the sunset promenades, the Sunday church services, the annual regatta – were mostly established as “traditions” within the very first years of the hotel’s operation.

The Ojibway was sometimes busy, sometimes bustling. On regatta days, it was even crowded. But often it was just what it was supposed to be – a lovely place to do nothing much.

It was as if Hamilton Davis understood that the bittersweet brevity of a northern summer always required some expansion. No one knew better than he did that things end, often more suddenly than anyone expects. After all, he was a man whose first wife died when she was only a young woman, and whose two sons, by his second marriage, did not survive their childhood. It must have been clear to him that the present, as vivid as it can be on one of those blue and wind-tossed Georgian Bay days, is never as unassailable as we might imagine.

The places we share with those who have gone before are often the places we most love. They are the means by which we belong to a story that is beyond ourselves. And perhaps for this reason, Hamilton Davis gave his place a past – the rustic style, the northern lore, the summer traditions – before it even had one. The Ojibway was always looking back – looking back, it seemed, to the days past recalling. From the beginning, it was as if his hotel had always been a hundred years old.

~

continue to { Chapter Two }