““It’s the freedom and openness of it all that gets one.” ”

“I got my ticket for Pointe Au Baril this morning," so noted May Bragdon in 1903, in one of the many diaries she kept throughout her life. The notebooks that she favoured – hard-covered, narrow-lined – are dry and brittle now and stored in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections of the University of Rochester. It’s impossible to read them without leaving a scattering of crumbled page edges and flakes of binding glue on the large wooden tables in the hushed reading room of the university’s library.

May Bragdon took naturally to Georgian Bay, later buying an island in the area in 1905. She named it Mandalay, after a poem by Rudyard Kipling about a young woman waiting for a soldier’s return.

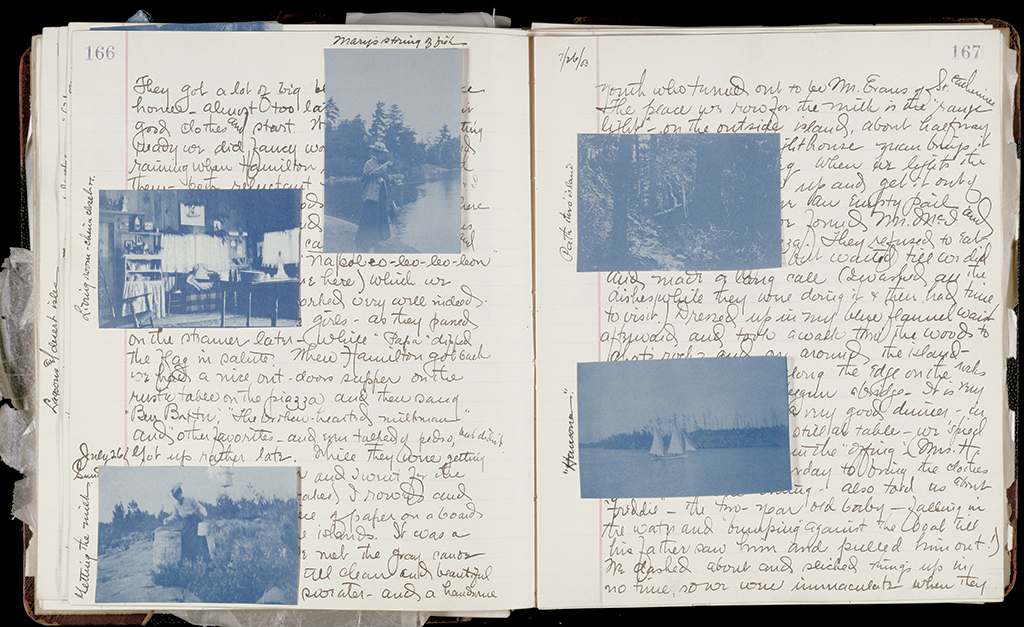

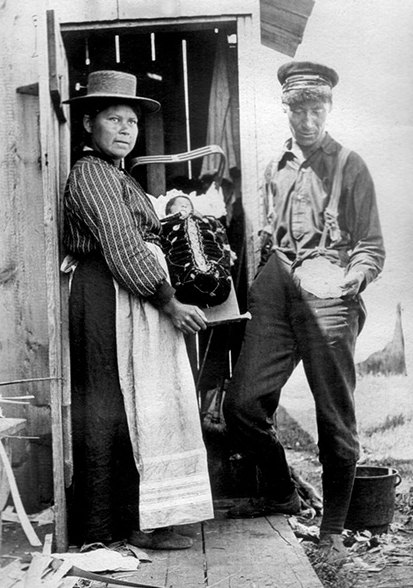

May Bragdon’s diaries are one of the few written records of the early days of the Pointe au Baril summer community, and the only ones that include much information about Hamilton Davis, the founder, the builder, the owner and the enterprising first manager of the Ojibway Hotel. Her entries provide a vivid picture of Pointe au Baril summers in the early years of the 20th century – a placid and untroubled way of holiday life in which people went bathing, not swimming; sat on piazzas, not porches; and gave their cottages and their islands quaintly amusing names. “Rowed over to Duazupleze and found the piazza full of Indians. Mrs. Pomawagawau and numerous descendants (only one of whom talked our language). She had a four-month-old papoose in a beaded case which she untied for our benefit…. They left while we were there and I Kodaked them. Later some of them came to St. Helena and the girls bought porcupine baskets and blueberries. Mrs. Mosher and Louise Gould came over and Mrs. Mosher, Helen, Laura and Christine went in, bathing off the dock…. We had a large and hearty dinner. Venison. And read and rested most of the afternoon.”

In May Bradgon’s diaries, she recorded her encounters with local Ojibway (above) as well as her trips to the range tower to pick up fresh milk. “The lighthouse man brings it down in the evening. We row up and get it out of the barrel and leave an empty pail.”

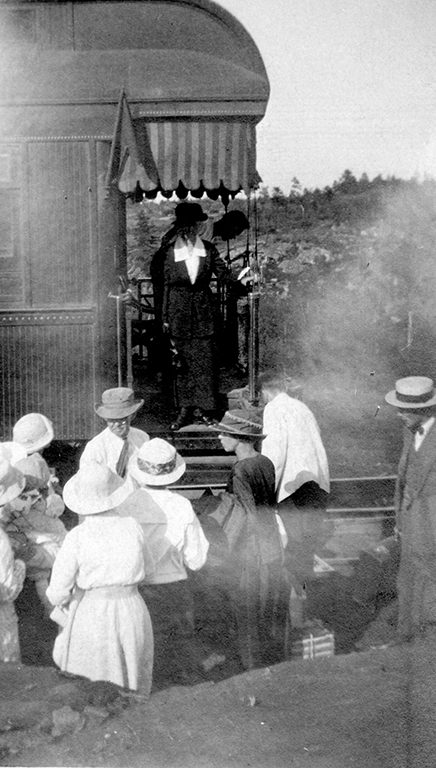

A keen observer and an assiduous diarist, May Bragdon took delight in recording her impressions of fellow travellers, such as the woman pictured above, on a steamship chair in front of the captain’s wheel-house.

May was a keen observer and an assiduous diarist. She notes, for instance, that Hamilton Davis’s skiff is double-reefed when he sets off to the Pointe for the mail and ice for the icebox. Yet, for all their keenly observed detail, the diaries can be maddeningly uninformative. For anyone searching for answers to basic questions of local history – When, for instance, did Hamilton Davis first arrive in Pointe au Baril and when did he begin to think about opening a summer hotel? – the pages upon pages of her entries remain as murky as the past from which they come.

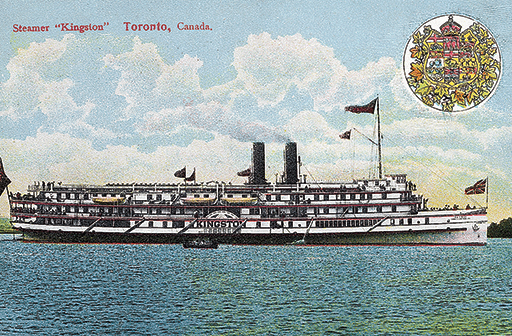

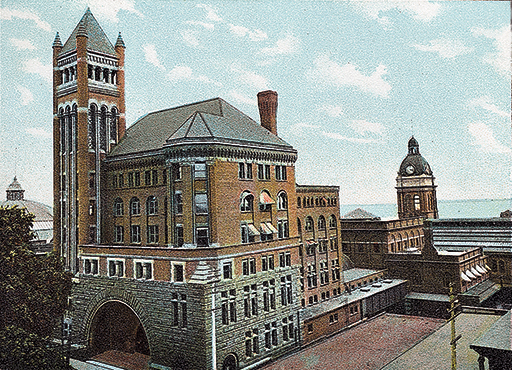

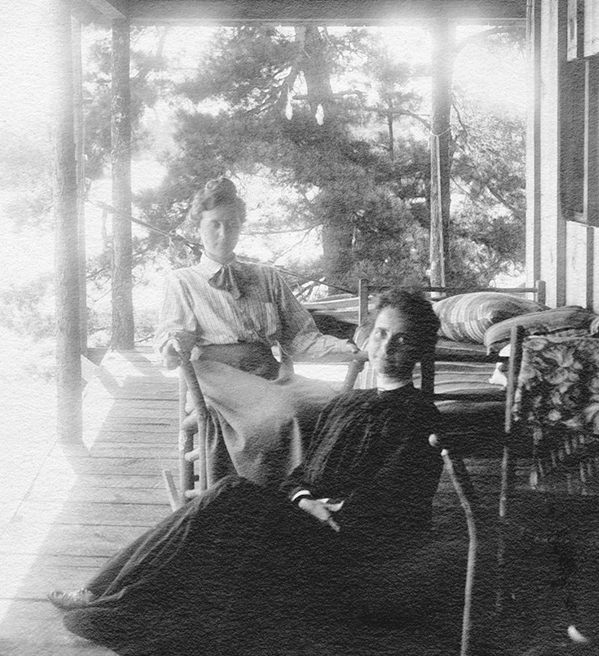

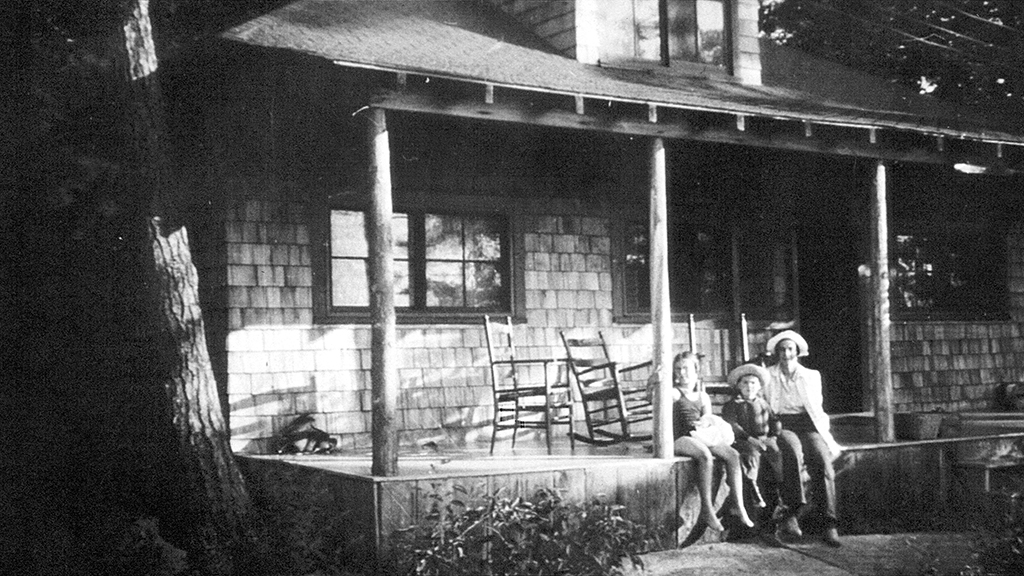

May Bragdon (seated right) often holidayed with a group of friends she called the “Perfects.” But she undertook her first trip to Pointe au Baril on her own. She crossed from Rochester on the steamship Kingston (top right). In Toronto she took note of the King Edward, “a very gorgeous new hotel” (middle right). She left by train for Penetang from Union Station (bottom right).

In Rochester, New York, the parents of Katharine, Charlotte, Hamilton, Helen and Frank Davis were friendly with May’s parents. Their homes were not in the same part of what was then a bustling, affluent town, but both families came from the same kind of pretty, middle-class Rochester neighbourhood. Hamilton and May were the same age, both born in 1864, but May was closer to Hamilton’s younger sister, Helen. Both were part of a close-knit group of women called the “Perfects.” Playing on both the word and the idea of “prefects” – for there was something simultaneously superior and schoolgirlish about her group of female friends – these 12 women set out, not to put too fine a point on it, to find themselves husbands.

In the summer of 1897, six Perfects – one of whom was Helen Davis – set out across Lake Ontario to spend several weeks on holiday at the Viamede Resort on Stoney Lake. May’s diaries describe how the ladies enjoyed the outdoors and became accustomed to roughing it a bit – which might explain why May Bragdon and Helen Davis later took so naturally to Georgian Bay.

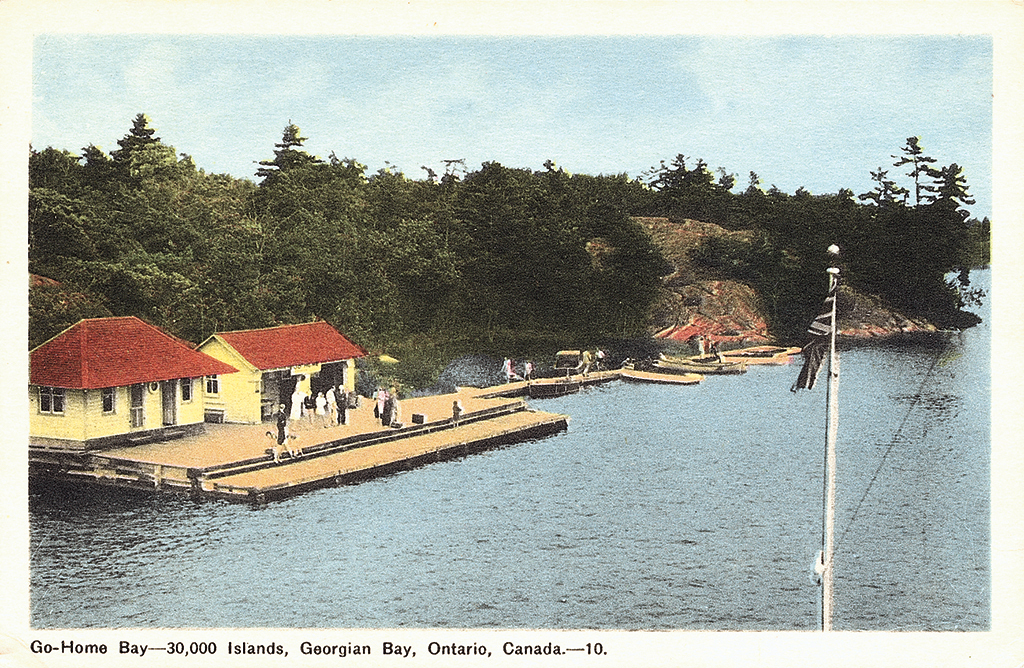

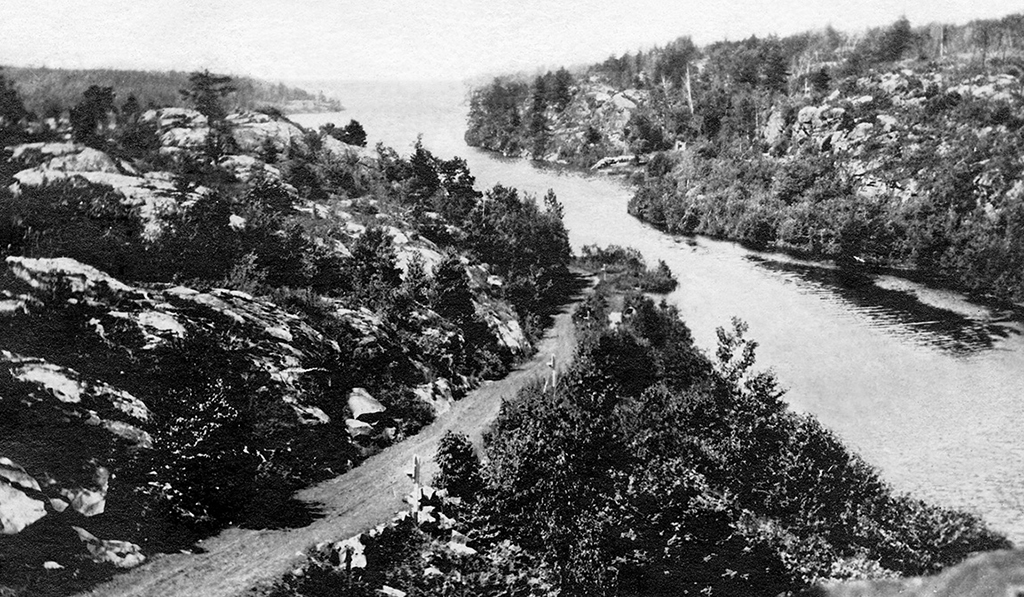

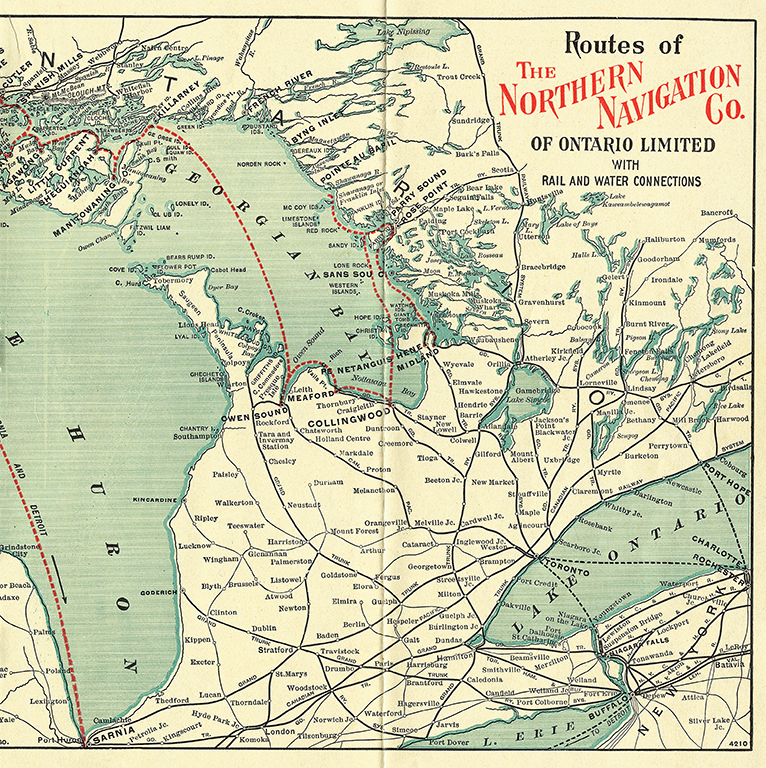

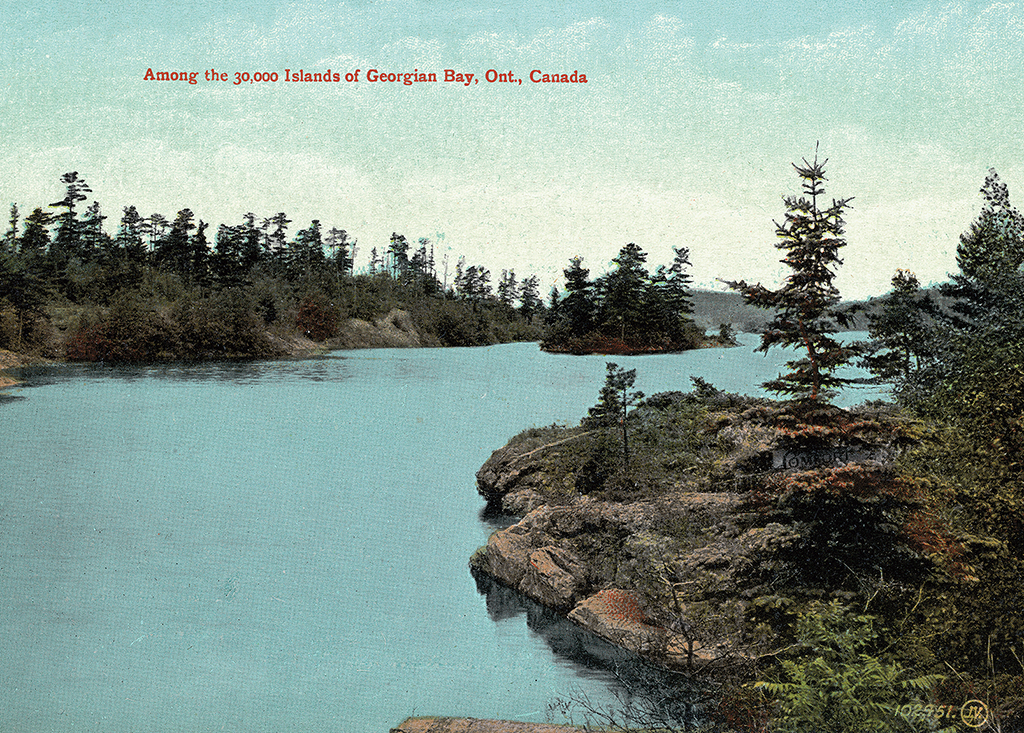

The City of Toronto (below) was built in 1895 and operated by the Northern Navigation Company of Ontario. Steamships brought supplies, mail and passengers to communities such as Go Home Bay (right) and Pointe au Baril.

Six years later, in July 1903, an entry in May’s diary describes her departure for Georgian Bay to visit Helen Davis. On a warm Rochester evening, Mrs. Bragdon accompanied her daughter to meet the steamer. “The Kingston was in and I got my nice outside stateroom on the starboard side, #104. Really luxurious for the lakes.” May crossed Lake Ontario overnight and arrived in the Toronto harbour at seven the next morning.

“I went on the Union Station bus – engaged a seat on the 11:35 train to Penetang, left my bag, had a very decent breakfast for 50 cents at the restaurant Track 3 and strolled uptown. Stopped at the King Edward, which is a very gorgeous new hotel.” May then boarded her train, which rolled north to Georgian Bay to meet the City of Toronto. “It did seem good to get on the boat at Penetang – as a good breeze blew the cinders away and a comfortable red chair awaited me. Yachts whizzed around us and there were big log booms.” As the steamer headed north, passengers were dropped off at their cottages and hotels.

The trip took about 24 hours, including an overnight at Parry Sound. “Weaving through lovely

islands. Once in a while a cottage or so.” When stopping at the Hotel Minnicognashene, “the stern line got fouled in the paddle, and we almost drifted onto a shoal.” The boat stopped in at Go Home Bay, which she described as “very beautiful indeed,” and then at the Pittsburgh settlement at Yankanuck near Sans Souci, where her observations were not so generous: “quite pretentious – a big clubhouse with a Negro on the steps.” It was at Yankanuck that “a gay party of attractive young people who had been singing all the way up got off” – rather to May’s relief, it seems. She was 39 – not gay and young anymore, and more inclined to enjoy the chug of the paddlewheel and the cries of the gulls than repeated verses of “The Broken Hearted Milkman” and “The Sweet Bye and Bye.”

It was getting dark as the boat began its approach to Parry Sound. All the cabin windows were draped. May was sitting on the deck and heard “the soft monotone of the pilot calling out, ‘Port, port, starboard, port,’ ” as they navigated though the narrow, rocky channels. She went to bed – “in Cabin 2.”

The first Pointe au Baril cottagers tended to build in the vicinity of the Bellevue Hotel (above, left). The cabin (above) of Helen Davis, a sister of the Ojibway’s founder, Hamilton Davis, was built on her island, St. Helena, named after Napoleon’s place of exile.

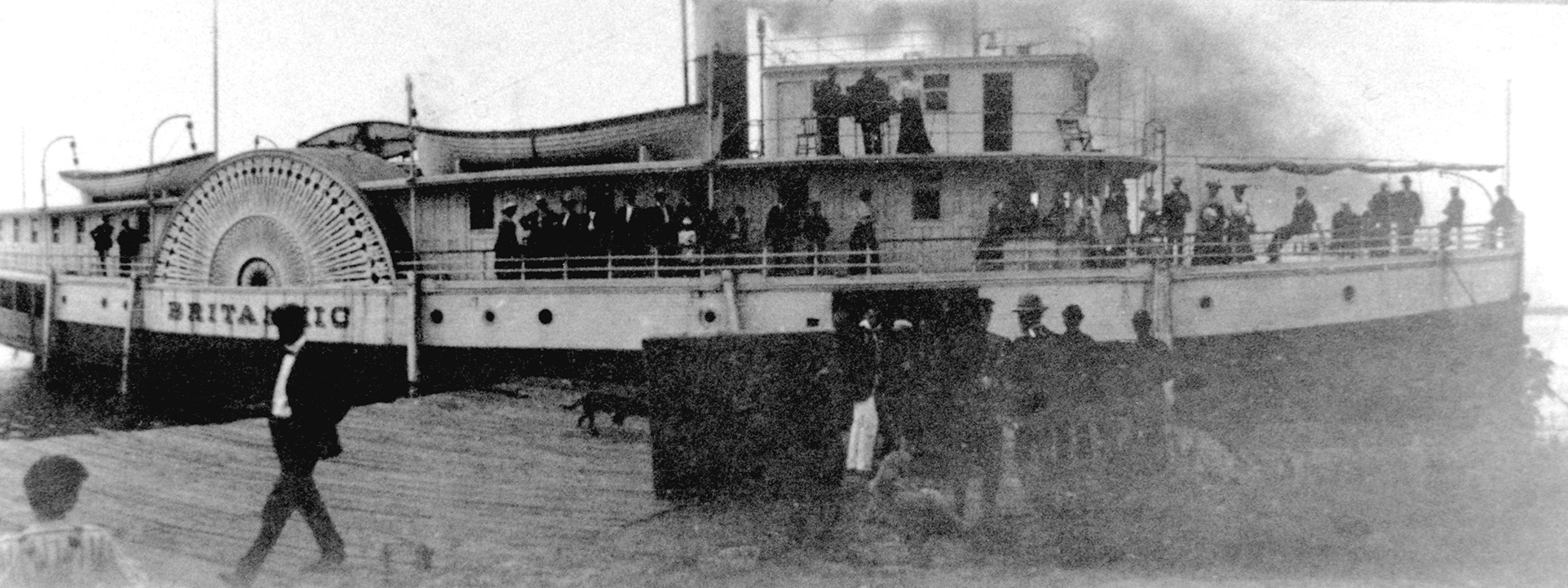

The next morning in Parry Sound, she was up and dressed before six. She disembarked and sat in the early-morning light on the dock and watched the City of Toronto begin its homeward journey to Penetang. At seven, the Britannic arrived in from Collingwood. “We ate breakfast on-board and then started north.” The Britannic stopped in at the Depot Harbour lumber terminus, not far from Parry Sound – “Such a queer place with ice docks and a railroad” – and then continued to Helen Davis’s new cottage on the island of St. Helena at Pointe au Baril.

In the glorious summer of 1902, Helen, in the company of a Rochester couple, the H. T. Moshers, had stayed at the Bellevue. As Ruth McCuaig wrote in Our Pointe au Baril: “Miss Helen Davis…in the course of a boat trip up through Georgian Bay, happened to stop off at the Bellevue Hotel across the channel from the Pointe au Baril lighthouse. The story goes that it didn’t rain for a month and she and her companions, an Eastman Kodak executive and his wife, stayed on and on exploring the nearby islands and channels by rowboat.”

The Bellevue was a three-storey, gabled frame building that opened in 1900. It was a good model for anyone considering opening a new hotel in the region, presenting a combination of graciousness and rusticity for American visitors looking for both. Its blustery proximity to the open water beyond the point of the lighthouse gave it the feel of a seaside resort – familiar to anyone who had holidayed on the coast of Maine. Helen Davis was obviously taken with the place. By the time she and the Moshers returned to Rochester, they, along with another intrepid couple, the Howsons from Chillicothe, Ohio, were more than a little enthusiastic about the beauty of Georgian Bay. Indeed, before their holiday was over, each had become the owner of an island.

One year later, in 1903, Helen asked her brother Hamilton to oversee the construction of the cabin on her island, St. Helena. That summer, their father came for a visit. So did her sister Charlotte. Helen also extended invitations to friends and fellow Perfects Mary May, Marjorie Fowler and May Bragdon.

Among the earliest islanders were the Howson family of Ohio. The summer visitors who signed their cottage guest book (below) would have travelled to Pointe au Baril from Parry Sound on the 151-foot steamship Britannic.

In those days, a sign posted prominently on an island usually marked a passenger’s disembarkation point. In this instance, however, the Britannic was hailed by a megaphone not far from St. Helena. May was led “down into the bowels of the boat” and she “slid out a door into a rowboat which Hamilton Davis was trying to steady against the ship.” This was not an easy manoeuvre. Once May was safely on-board and once the rowboat pushed away from the side of the Britannic, she heard one of her former fellow passengers say: “Do you wonder that people get drowned?” Her bag was delivered to the steamer’s next stop, at the Bellevue Hotel. Later that night, Will Oldfield, whose family owned the Bellevue, a fishing operation and a delivery service at the Pointe, brought the luggage, along with some lumber Hamilton had ordered, to St. Helena on his tug.

May stayed at Pointe au Baril for two weeks that summer. Her journal entries read not like the diary of a middle-aged woman, but like that of a teenager – so wide-eyed and eager was her enthusiasm. “All of this happened on the side away from St. Helena,” so she wrote a little breathlessly of her disembarkation from the Britannic. “So I only saw it revealed when the steamer started off. The girls stood in rows waiting for me – Helen, Charlotte, Mary May and Marjorie Fowler. Also Papa Davis. The cottage and the island are beautiful. A big Welcome made in oak leaves greeted me…when I entered the door.” May relished the sense of family that she found in Pointe au Baril. “The living room and the piazza are delightful, and for that matter so is the kitchen and bedrooms and all. A nice fish dinner which Mary and Hamilton got up at five to catch, and blueberries which Chat and Marjorie had been picking, and such pretty china, too.”

May Bragdon was much taken with the natural splendours of Pointe au Baril. But she was just as enthusiastic about Hamilton Davis, nicknaming him “The Skipper,” and “Kodaked” him in his skiff, Bouncing Bett.

In May’s diaries, it is possible to read her description of outings with Hamilton Davis – the morning rowboat trips; the moonlit paddles with Hamilton to discuss his plans for a summer hotel and to look at the stars; the afternoons spent sailing with him in his brown-sailed skiff as he explored the islands and the channels – and to miss the obvious. How much her words – “but the night, oh the lovely night…” – betray her unfulfilled hope that Hamilton would pay her special attention. It is often difficult to gauge her true feelings.

But was Hamilton Davis so preoccupied with his plans for the Ojibway Hotel that he was entirely oblivious to the meaning of May’s frequent company and of her eagerness to assist him? If so, his lack of romantic attention never altered her opinion. She remained a fan. Her view of him was consistently admiring and positive. He comes across as a dynamic and attractive figure. May called him “The Skipper,” as he was always escorting the ladies at the helm of his little boat. In Our Pointe au Baril, Ruth McCuaig tells us that by the time Hamilton was casting his “eagle eye for detail” over the busy and almost immediately successful Ojibway Hotel, he was “affectionately known as Hammy.” But in the summer of 1903, in the entries May made in her diary, nothing so irreverent was permitted. “Hammy” wouldn’t do. It was Hamilton. Or it was The Skipper. She made it clear that as far as May was concerned, Hamilton Davis was a serious man. He was a man with prospects.

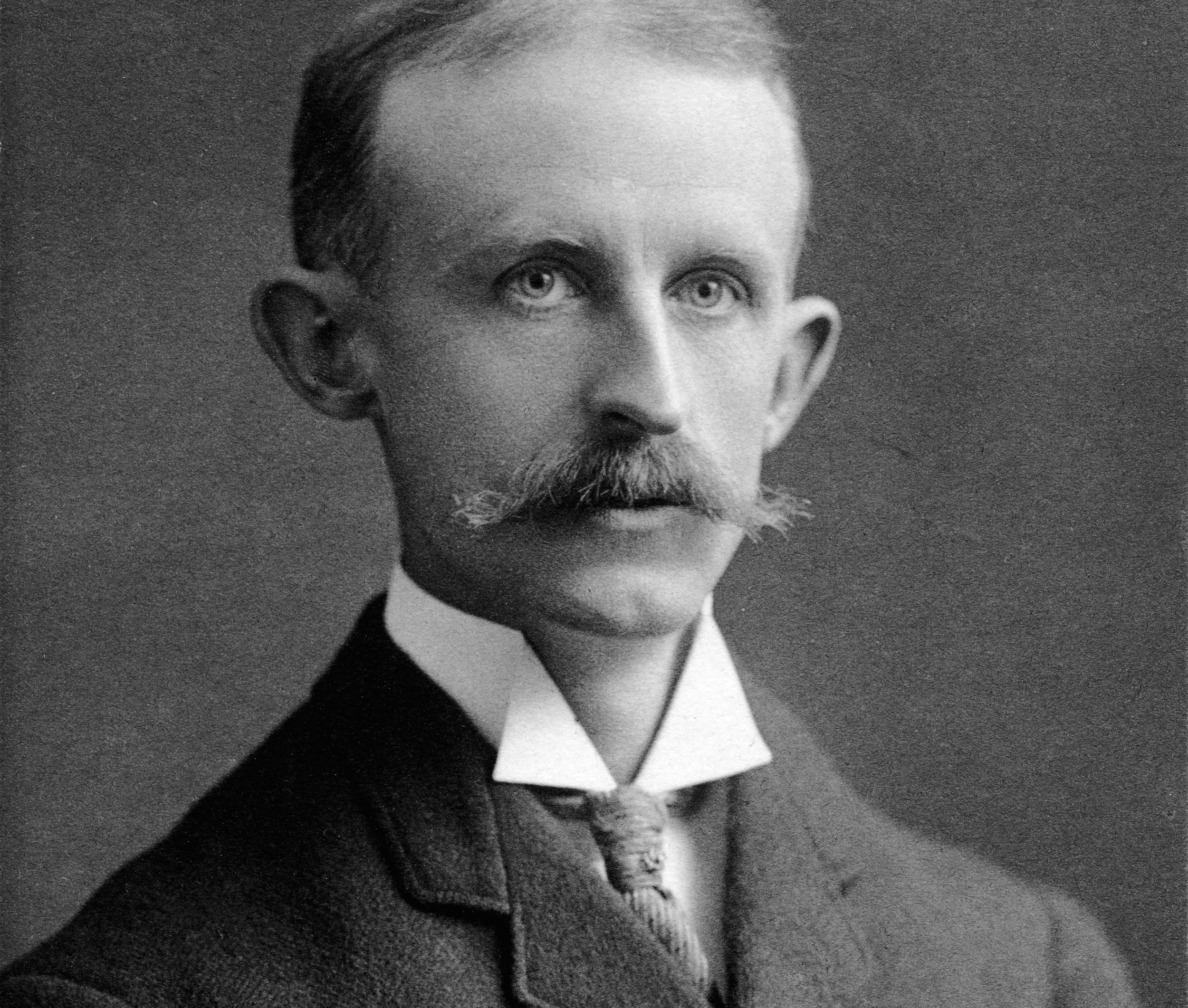

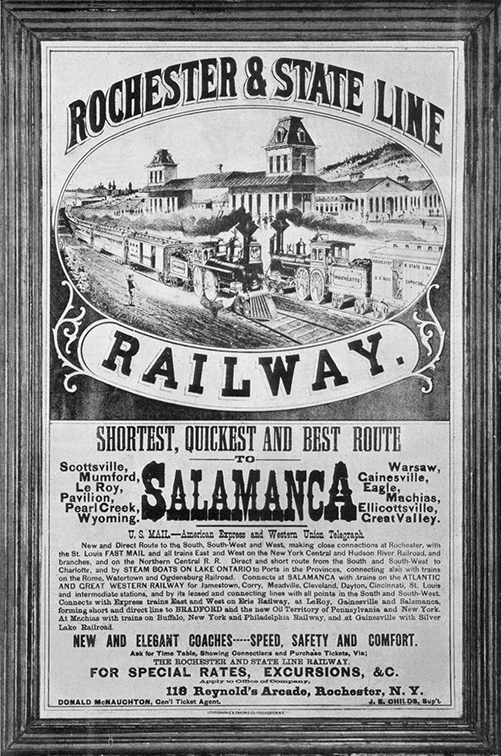

Not very much is known about Hamilton Davis prior to his arrival in Pointe au Baril from Rochester. What little trace of himself he left in the last two decades of the 19th century suggests a courteous, perhaps slightly stiff young man who had not quite found his way in life. Born in 1864 in Dunkirk, New York, he moved to Rochester and finished school there when he was 14. He worked as a clerk in a shirt shop from 1880 to 1887. Census records show that for the next two years, he was employed as a salesman. In 1889, he began working as a train agent for the Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburgh line. Curiously, Hamilton’s name then disappears from the U.S. census records. By the time Pointe au Baril entered his life, he was almost 40 and single and was living in his parents’ house.

Hamilton was thin, wiry and strong. He had something of the military in his features. He was handy and was working on projects all the time – rustic shelves, a pretty bridge, an icebox for St. Helena and the building of docks. Efficient and proper, though not without a quiet sense of humour, he was, by the summer of 1903, already thinking about an enterprise that seems remarkably ambitious.

A well-known local landmark was the rustic bridge (pictured at right, beside Hamilton Davis’s skiff) that linked William Sing’s islands. A prominent real estate agent, Sing benefited directly from the railroad’s arrival in 1908. (View from trestle, bottom right.) Hamilton Davis also anticipated the train. He worked as a railway agent in Salamanca, New York, before opening the Ojibway.

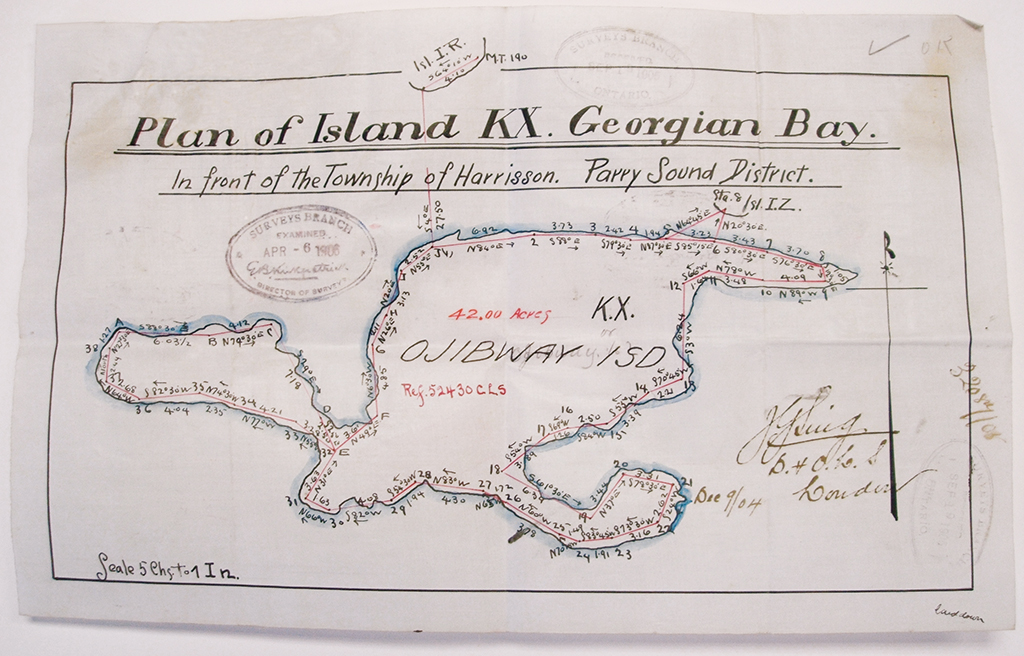

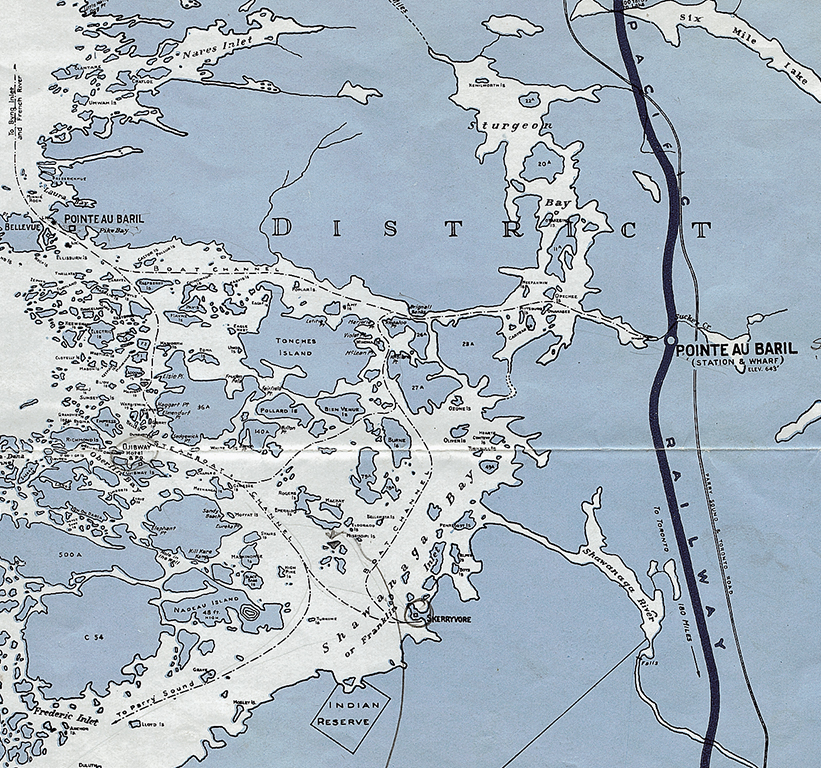

May Bragdon’s copy (left) of Hamilton Davis’s map showed the area south of the lighthouse in 1903. Island KX, later known as Ojibway, was surveyed by J. G. Sing in 1904. In 1906, Hamilton Davis received his patent (above) from the Crown for Ojibway Island.

May noted: “Sunday, July 26. Got up rather late. While they were getting breakfast, Hamilton and I went for the milk to make pancakes. I rowed and he took along a piece of paper on-board to make a map of the islands. It was a gorgeous morning.” For a freehand rendition, Hamilton’s map was remarkably accurate, and on one of the islands, not far from St. Helena, with a striking view of the lighthouse, he printed the word “Hotel.”

“There’s just bare rock, weathered granite with a ragged scalp of moss and thumbtack trees.”

”

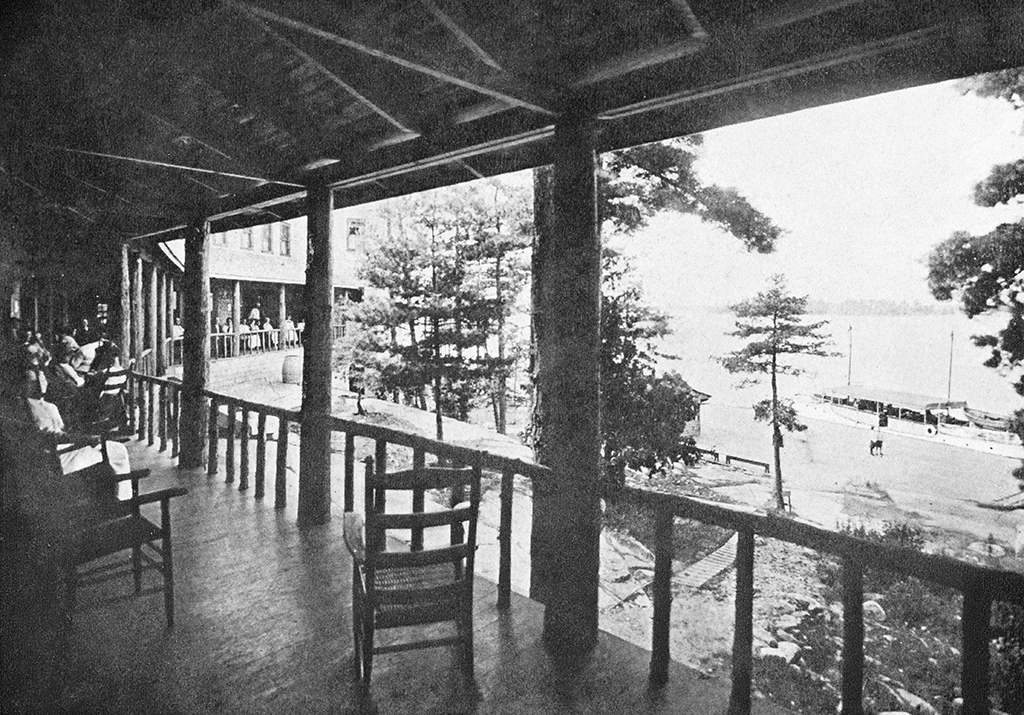

A view to the open water featured the Bellevue Hotel to the left and the lighthouse and John McIntosh’s fishing facilities to the right. Relaxing on the front porch was a prime activity for vacationers in Pointe au Baril.

But as entrepreneurs know all too well, the first plan is seldom the one that gets off the ground. That October, the island that Hamilton had so confidently claimed as his site for a future hotel, was purchased by Ward Leonard of Bronxville, New York, from two steamer captains. Leonard named it Mayne Island and made plans to build a grand two-storey house.

There was no shortage of other islands to choose from. But Hamilton needed one that was big enough and pretty enough to suit his plans. A sunset view was important, as was deep water and easy access to the boat channel. His eventual choice was ideal. A 42-acre island identified on the 1904 survey as “KX,” which Hamilton first named Pine Tree Island and later changed to Ojibway Island. It was on the main channel used by the steamers travelling from Parry Sound up to Pointe au Baril, and farther north to the French River and Manitoulin Island. There was also protected water access from what in those days was called Sucker Creek, but which in 1908 became the site of the Pointe au Baril railway station.

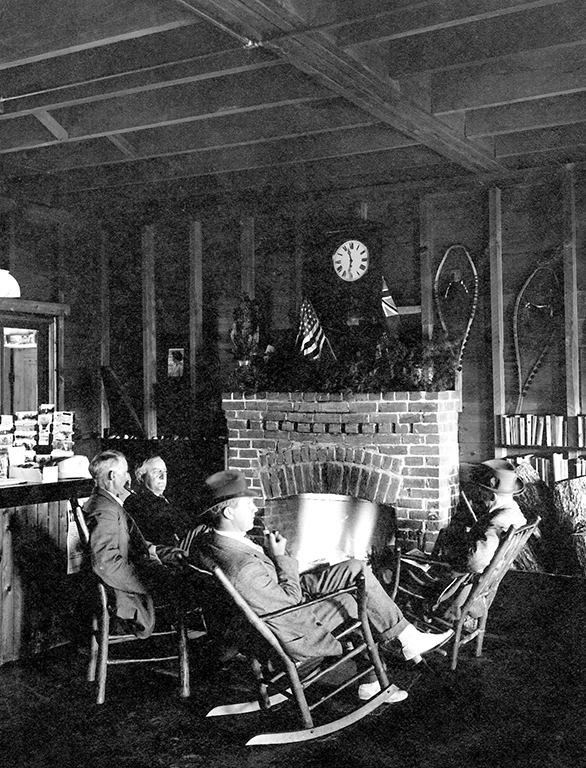

Helen Davis had fallen in love with Pointe au Baril, but it was her brother who wanted to pursue the entrepreneurial possibilities of the area. On his paddles and rowboat outings, he must have realized that canoeing, berry picking, fishing, watercolouring and generally enjoying the tranquility of what was known as the “veranda life” of a comfortable northern hotel would have enormous appeal to middle-class vacationers, particularly those from the northeastern corner of the United States.

It was a bit of a hike, of course. But that was to be expected. By modern standards, the trip to

Georgian Bay was long – two, possibly three, days could be spent in transit – but it was not particularly arduous, as May’s diaries attest. Baggage was taken care of. Meals and refreshments were provided. There were sleeping berths. The passing landscape was picturesque. Indeed, observation cars of the railway trains and the pleasant decks of the steamers were a much more relaxing part of a summer holiday than today’s crammed automobiles and traffic jams.

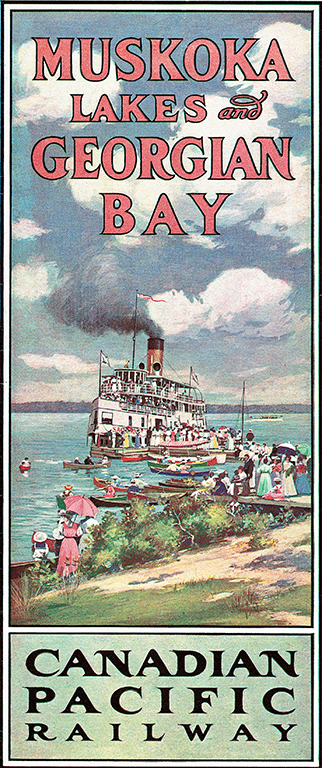

The Northern Navigation Company, formed in 1899, conveyed passengers in considerable comfort to remote destinations.

An adventure among pine-clad islands and rocky shores was very much in vogue in the early years of the 20th century. Typical of the excitement was the boosterish prose that accompanied speculation in local papers of railway expansion and what was hoped would be the ensuing bonanza of travellers: “Most people are acquainted with the Muskoka Lakes but as yet only a limited few are aware of the beauties of the Georgian Bay shorelines…. The facilities for boating, rowing, canoeing, and motor-boating, are unsurpassed, the fishing is excellent, the scenery superb, the air clear, pure, and free of microbes, the water clear, clean and pure, no storm can reach the quiet inner channels of this paradise.”

While most of the men spent their days fishing, the Ojibway’s other guests passed their time enjoying the “veranda life” of the

hotel. The Ojibway’s west addition (in the background) was completed in 1913.

“The Ojibway circulars are out,” wrote May Bragdon in a diary entry in the spring of 1906. On June 23, the new hotel opened its doors.

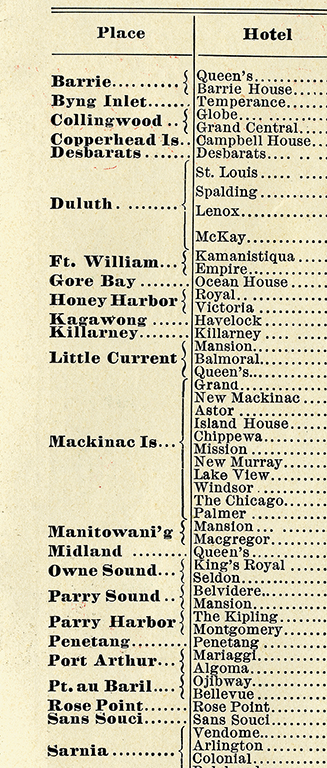

Northern hotels had already opened with considerable success in the Muskokas: Rosseau House, better known as Pratt’s, had been built and run by a New York hotelier since 1870. Both Clevelands House and Windermere House opened in 1883; Beaumaris House, Summit House and Deerhurst followed. In February 1907, on a single page of the Parry Sound North Star, above a notice for J. H. Knifton – the agent for the Canadian Northern Ontario Railway, the CPR and Ocean Steamship Lines – there appeared ads for seven hotels in the Georgian Bay area: the Victoria House, the Ahmic Harbour Hotel, the Whitestone Hotel, the Dunchurch Hotel, Montgomery House, the Hotel Kipling and Maple Lake Hotel. Because roads to these establishments were either difficult or non-existent, the usual pattern of travel for summer guests journeying to Georgian Bay or Muskoka created a partnership between railways and steamships that resulted in the establishment of the grandest of the summer hotels.

In 1901, the Royal Muskoka Hotel opened on Lake Rosseau. It was an island hotel large enough to accommodate 2,000 guests at its Friday-night dances, and it was jointly owned by the Grand Trunk Railway and the Muskoka Lakes Navigation and Hotel Company. It was so grand an establishment – its Italianate turrets and Mediterranean tiled roofs made it look like the kind of hotel found in Palm Beach – that it commanded the same kind of press attention that was being devoted to the magnificent Canadian Pacific hotels across the country.

Canadian tourism was touting itself – not without reason. Railways were expanding and it was known that the CPR was going to push north soon from Parry Sound to Pointe au Baril and beyond. The 30-room Bellevue Hotel was usually full. A year before the Ojibway Hotel opened, a story in the North Star reported that “while in Muskoka there is room for thousands of visitors, there is room for millions in Georgian Bay.” The article concluded with what was almost an advertisement for the region – directed at people such as Hamilton Davis: “Good openings for capitalists.” The potential of Pointe au Baril must have been clear.

The steamers, operating out of Penetang, Collingwood and Parry Sound, were there; the railway beyond Parry Sound would soon be there; the beautiful landscape and the fishing were there; and the market – middle-class Americans in search of an affordable vacation in the romantic north woods – was certainly there. Helen Davis may not have been thinking about her brother’s career when she decided to purchase an island not far from the Bellevue, but as things turned out, the locale she chose could hardly have been more prescient.

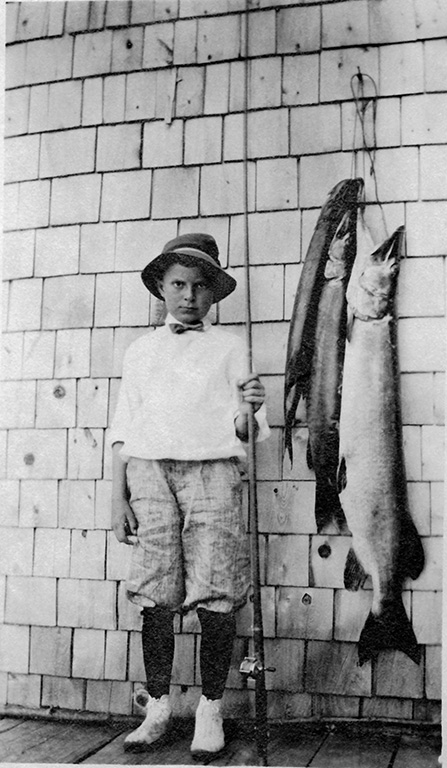

There was no doubt that the fishing at the Ojibway was excellent. But Hamilton Davis knew that his hotel had to appeal to fishermen, even the younger ones, and non-fishermen alike. Picnics and berry-picking outings were also popular.

The Ojibway opened in 1906 and it seemed to spring fully formed into Pointe au Baril summer life. Its first season was a success. One of the guest lists from the inaugural year suggests a considered marketing and advertising campaign: the clientele was drawn from so large a geographic base it seems clear that Hamilton Davis had invested a good deal of time in working the network of railway agents that he knew so well. Train agents were the travel agents of the day, recommending destinations to would-be tourists. The hotel’s early guests came from Rochester, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Oberlin, Brooklyn, New York, Jackson and Cleveland, as well as Kingston, Ontario.

That summer, an article about the Ojibway appeared in the North Star. There is nothing tentative about the hotel’s claims; the place already seemed to be certain of its personality: “At Ojibway Island, rumour has it there is always a breeze, and cool shade is always to be found under the fragrant pines. And something more than rumour says that the ‘Ojibway House’ has no superior on Georgian Bay for sunset views, good cooking, cleanliness and the comfort of its guests. The moss-covered rocks in the shade of the pines make most attractive spots for restful hours with a book. For the more strenuous guests, the sandy bathing beach and boating of all kinds are always available. During the weeks just past, the house has been filled to overflowing and the only individuals allowed a landing place on the wharf are the record-breaking black bass which do not have to be tempted to accept the charming hospitality of the Ojibway. A 22-pound Muskalonge [sic] has taken the hook in the past few days. Fish dinners have attained perfection here. Now is the time when the hay-fever victim hastens to Georgian Bay assured of absolute relief. When September comes with the beginning of the cool autumn days, the anglers of the island with gun and guide will find the wild duck and partridge winging their way to their favourite haunts about the island, and poor indeed must be the shot who fails. What can offer more attractions than a charming island, a modern hotel, admirably conducted, congenial companions and last, but not least, Imogene, the island cow?”

Hamilton Davis (above, left, with pipe) oversees the arrival of the hotel cow.

The Ojibway employed as many as 25 fishing guides a season. Many camped with their families on the back of the island for the summer.

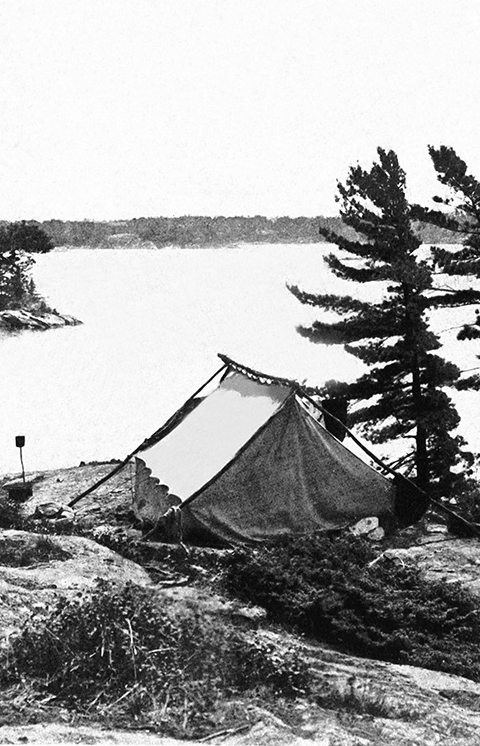

The cow was kept in a stable on the island so that guests could enjoy fresh milk and cream, and some years a pig was imported to the island to deal with the garbage. Guests also enjoyed what the hotel had claimed they would: the fishing, the bathing, the bracing air, the peace and quiet. By 1907, in the hotel’s second season, an announcement in the North Star reported that “the enterprising manager already finds it necessary to plan for an enlargement of the house during this coming winter. Already this year, the volume of business is larger than last year, in spite of the very irregular boat service, the Britannic sometimes failing to call and the Mazeppa being laid off for repairs. The rooms are all practically engaged for the next month and Mr. Davis has to resort to the use of tents, and by this means he hopes to accommodate all who may come.”

Hamilton Davis’s belief in his hotel would prove to be as well founded as his hunch that it would become the centre of a thriving summer community. Among the papers that Ruth McCuaig left in her research files is a Pointe au Baril Islanders’ Association map, published in 1959. On it, her husband, Jack, has drawn concentric circles to mark the density of the summer community. The widest of his circles spans three miles. They descend in size by half-mile radii. Jack McCuaig’s diagram more or less defined the Pointe au Baril summer community as it existed more than five decades after Hamilton Davis first began exploring the islands. At the centre of the pencilled circles is the Ojibway Hotel.

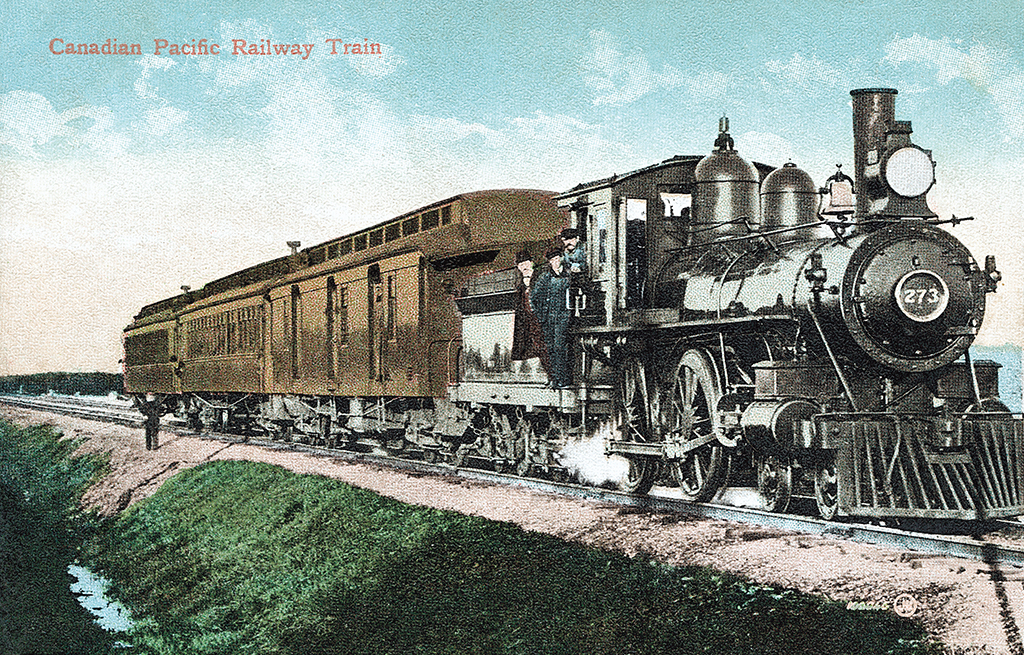

Travelling north in the era of the train.

All Aboard –

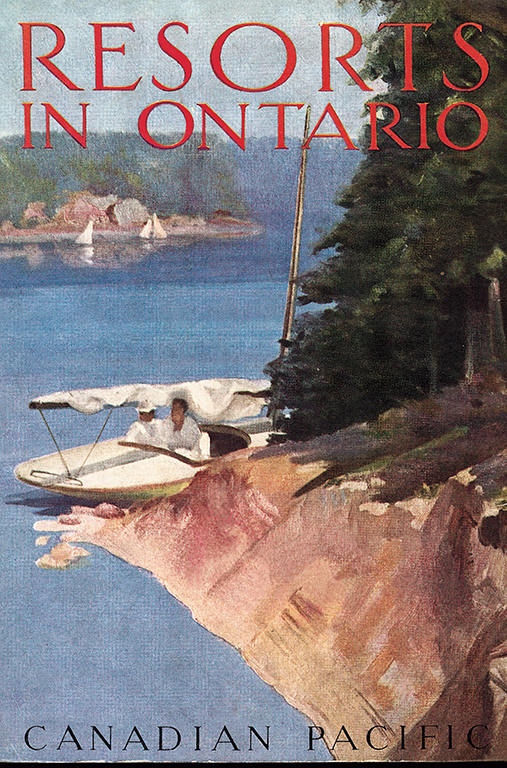

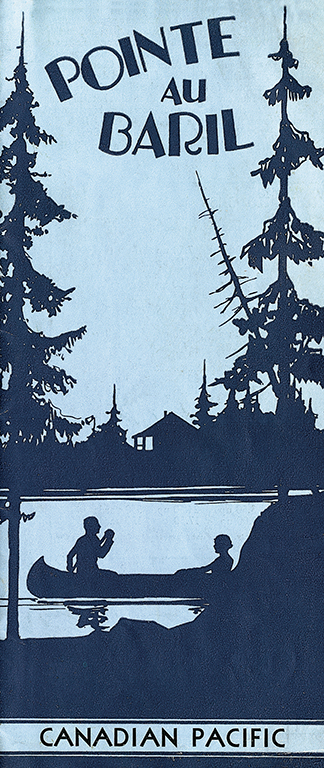

In 1916, when Paul Pope and his family were returning to Boston from their annual summer holiday in Nova Scotia, they noticed that their ship was zigzagging on the Atlantic as it approached port. This seemed odd. But it was when they were safely in port that the Popes learned from the customs officer that the captain had been taking evasive action against a German U-boat. Six vessels had been reportedly sunk that night. That was enough for the Popes. Their next summer holiday – to the Ojibway Hotel, in faraway Pointe au Baril – was decided upon by consulting railway brochures. Railway agents were the travel agents of the day, and the brochures printed by railroads were handsomely produced and informative, if not always entirely accurate. Georgian Bay, so travellers consulting a CPR brochure in 1916 were informed, was “warm and pleasant for bathing; unlike most localities of rocky formation, many islands are partially surrounded with sandy beaches."

““After the train stopped the only sounds were the whippoorwill and snoring from behind the heavy green curtains of the berths.””

Above all, the Ojibway was comfortable.

A Summer Place –

It has been called Shingle

Style – a term coined by Professor Vincent Scully of Yale – and it reached the height of its popularity between 1880 and 1905. It was an architectural response to ostentation and the social formality that had lingered on throughout the early 19th century. As exemplified by the most beautiful cottages in the Pointe au Baril area, buildings were constructed to blend into the terrain, not obliterate it, and to complement the landscape, not overpower it.

The Ojibway was a model of Shingle Style, with its unpainted cedar shakes and window trim painted dark green, and apparently Hamilton Davis was astute in gauging the tastes of his clientele. So immediately successful was the hotel that it expanded twice in its first seven years of operation. The east wing opened in the summer of 1908, and the west wing and tower, financed with a $2,000 mortgage, were completed in the spring of 1913.

““No automobiles. No hay fever. No noise.

No intoxicating liquors sold on the Island.” ”

~

continue to { Chapter 3 }