~

THE SONG OF HIAWATHA INSPIRED MANY TO SPEND SUMMER HOLIDAYS IN THE NORTHERN WOODS.

If Comfort were ever needed for writers whose work is not well received by critics, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha would provide it. This epic poem, published in 1855 and based on the Ojibway legends compiled by the celebrated American ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, was not greeted warmly by reviewers. But Longfellow had the last laugh.

The Song of Hiawatha was an immediate commercial success. Its influence was astonishing, reaching far beyond Longfellow’s lifetime and becoming so imbedded in North American culture it was not always viewed as a work of fiction. It spawned an enthusiasm for Native culture that was sometimes misinformed and romanticized, sometimes heartfelt and sincere. Tom Symons, a past president of Trent University and the son of Harry Symons, the author of Ojibway Melody, said that the Hiawatha craze “was certainly part of what inveigled so many of the camps and groups to the Pointe au Baril area. It was not so much a factor in Canadian thinking. But the Americans often spoke of Longfellow.”

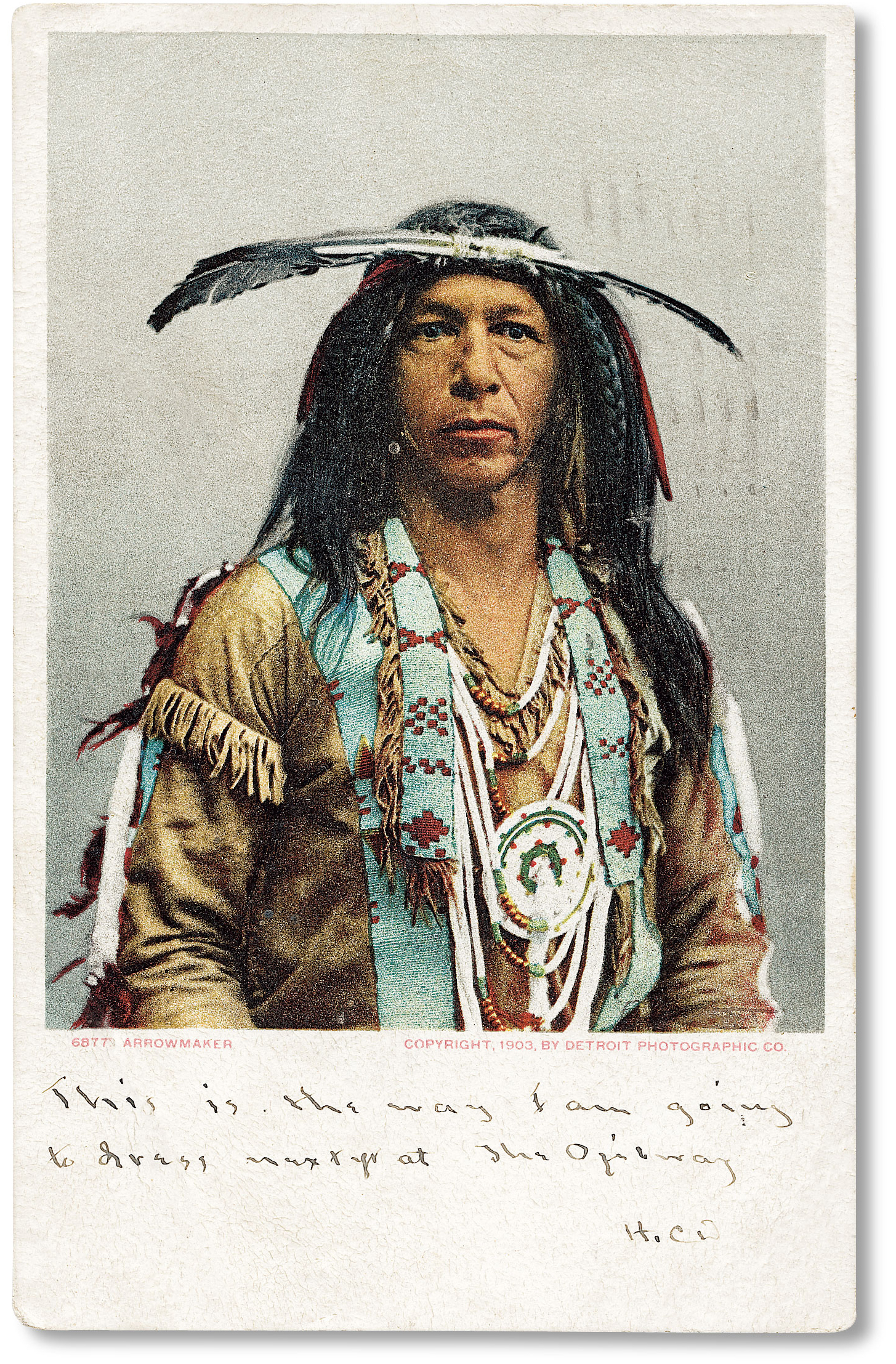

“This is how I am going to dress next year at the Ojibway,” so joked Hamilton Davis in 1906. The image on the postcard (left) was intended to be that of Arrowmaker, a character in the Longfellow poem The Song of Hiawatha. But Davis was quite serious about the impact of the Hiawatha legend on his clientele. He used Arrowmaker as the logo for his new hotel.

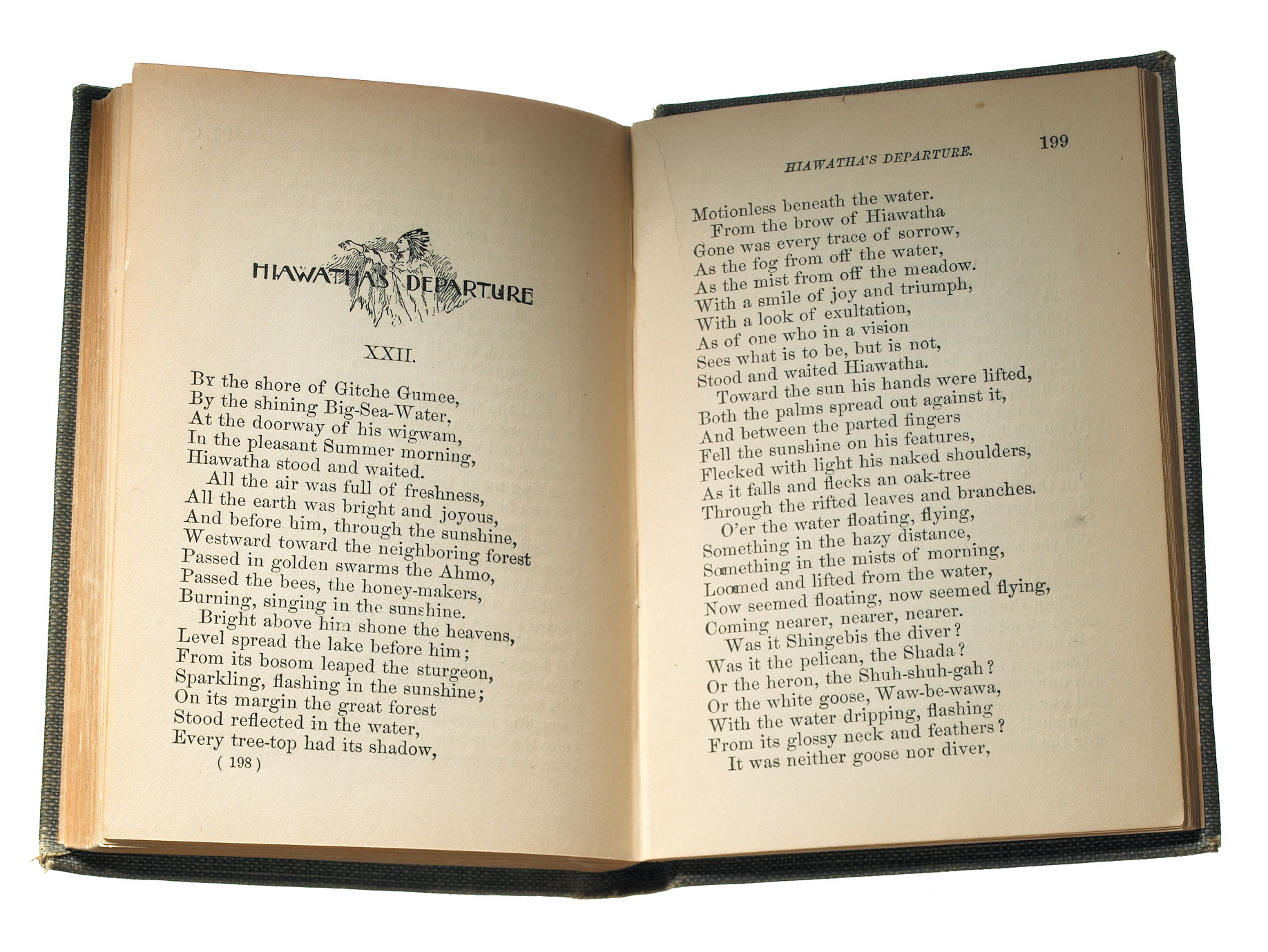

Longfellow always said that the name of the hero of his epic poem was pronounced Hee-a-wa-tha. The author’s preference never caught on. But the poem certainly did. A classic of American literature, it had an astonishingly wide readership and innumerable printings. This edition (top) appeared 40 years after its original publication.

In the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th, an authentic, untamed wilderness was still a reality. At the same time, American urban life, particularly in the east, was already becoming crowded, polluted, stressful and unforgiving in the demands it made on the lives of overworked city dwellers. The life of North American Natives as portrayed by Longfellow – the dignity of their spirituality and their harmonious relationship with nature – held enormous appeal to an educated and relatively affluent middle class.

As part of this cultural enthusiasm, images of North American Natives became increasingly popular. Advances in photography and in printing techniques made these widely available, often through the penny postcard. Among the most successful producers of such images was the American photographer William Henry Jackson. By the end of the 19th century, his images – often posed, not always entirely authentic and sometimes drawing directly on the legends of Hiawatha – were being widely distributed. In 1906, Hamilton Davis, the founder of the Ojibway Hotel, sent a postcard to his bride-to-be, Millie McIntosh. “This is how I am going to dress next year at the Ojibway,” Davis wrote. The image was Jackson’s “portrait” of Arrowmaker, the father of Hiawatha’s bride, Minnehaha, in Longfellow’s poem.

Jackson’s picture of Arrowmaker was produced by the Detroit Photographic Company in 1903. It played a little loose with details: the tribal costume is less that of a Woodlands tribesman and more Plains in its design and ornamentation. Still, it was exactly the kind of commanding, dignified image that Hamilton Davis needed to advertise the stately northern characteristics of his new hotel. He had named it the Ojibway after all, and it was not lost on him that many of the cottagers in Pointe au Baril used names from the Longfellow poem for their newly purchased islands: Minnehaha and Wabun are cases in point. The summer the Ojibway opened, Hamilton’s mother wrote on an identical postcard, telling him that his sister Charlotte, “has sent to see if she can buy you some of these cards.” Clearly, Hamilton Davis understood that any allusions to the Hiawatha mythology would serve him well. From the beginning, he seemed to know exactly how to market his new hotel. William Henry Jackson’s interpretation of Longfellow’s legendary Arrowmaker was used for the logo and the letterhead of the Ojibway.