~

MARION THAYER MACMILLAN DID SOMETHING UNUSUAL AT POINTE AU BARIL. SHE LOOKED.

For the 20 years between the two wars, Marion Thayer MacMillan, a professor of psychology from Ohio, and her husband, Dr. Wade MacMillan, summered in Pointe au Baril. They spent their first year at the Ojibway Hotel, but for their subsequent holidays, they rented a small cottage that the Ojibway dock master, Bert Bruckland, had built for his wife. In their cedar-strip canoe, the Sprinx, the MacMillans paddled the short distance to the Ojibway every day for breakfast and dinner, but the kitchen staff always packed them a hamper for their lunch. They had things to do.

To view the “water picture” images at Pointe au Baril, the conditions had to be perfect. There could be no wind and no waves. Even the ripple created by a passing canoe could disrupt the totemic designs that Marion Thayer MacMillan and her husband, Dr. Wade MacMillan, called “the discovery.”

Every day, Wade paddled from the stern of the Sprinx. Marion sat facing him, on a boat cushion against the ribbed bottom of the canoe, with her parasol, and together they explored the maze of islands and shoals of Pointe au Baril. They were in no hurry: hurrying, in fact, was entirely antithetical to what they were doing. They were looking.

This passion required no justification beyond itself. The MacMillans owned no camera, brought no watercolours. They were like aficionados in an art gallery intent on the finest brushwork. They kept the Sprinx as close to shore as possible, carefully studying the details of rock and shadow, lichen and moss. Describing a thrill that is all but lost in the speeding age of the Jet Ski and Donzi, she wrote: “It is exciting to watch the shore change as the wind slowly subsides at dawn or dusk.”

It was during their third summer in Pointe au Baril that Marion made what she would come to call “the discovery.” On a particularly clear, calm evening, just as the sun was setting, she looked toward the island they were slowly passing, and instead of seeing a shoreline and a reflected shoreline, she perceived the two elements of her view as a single entity. And then, tilting her head, she transformed the horizontal into a vertical design.

“Slender water plants, reeds and grasses, with their reflections, present a variety of geometrical patterns, double curves, heart shapes, triangles, circles.” Where once she had seen a lined rock and its reflection, she could now sometimes see, in the double image, totemic faces and figures.

“With a shout of surprise,” wrote Lewis Mumford in a New Yorker review of these startling photographs, “one discovers when one turns the head quarter way round that the results are achieved by photographing rocks that stand above water clear enough to give a complementary image.”

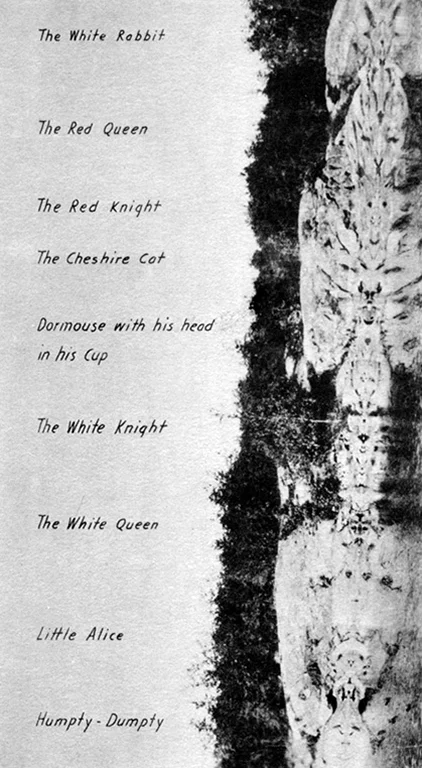

This changed everything for the MacMillans. It became important to them to record this phenomenon, and they first turned to Irene Davis, the second wife of the Ojibway Hotel’s proprietor. Irene was an amateur photographer. “To her I owe the first and some of the best of our pictures,” Marion wrote. But it was her second photographer, Dorothy Rolph, a designer from New York City, who brought the MacMillans’ discovery the greatest acclaim. Dorothy Rolph was a regular guest at the Ojibway and eventually showed her black-and-white poster-sized shots of these mysterious, sometimes unsettling, images at a gallery in New York. “On the surface, one beholds a magnificent totem pole, a Cambodian column or a head by Brancusi,” wrote Lewis Mumford in a New Yorker review.

Marion argued that their discovery was in some way a clue to the origins of the carefully balanced design of Aboriginal art. These strange and weirdly beautiful “water picture” photographs hung for many years in the dining room of the Ojibway Hotel.

But Marion Thayer MacMillan was most haunted by what she could not preserve: “These water pictures,” she wrote, “are most impressive on a bright night when the weird faces peer at you from a moonlit pool and the faint movement of your paddle makes them grimace or cause an arm to beckon mysteriously. Then the effect is spectral indeed…. But these moonlit monsters that show supremely as darkness falls can – alas! – never be caught by the camera.”