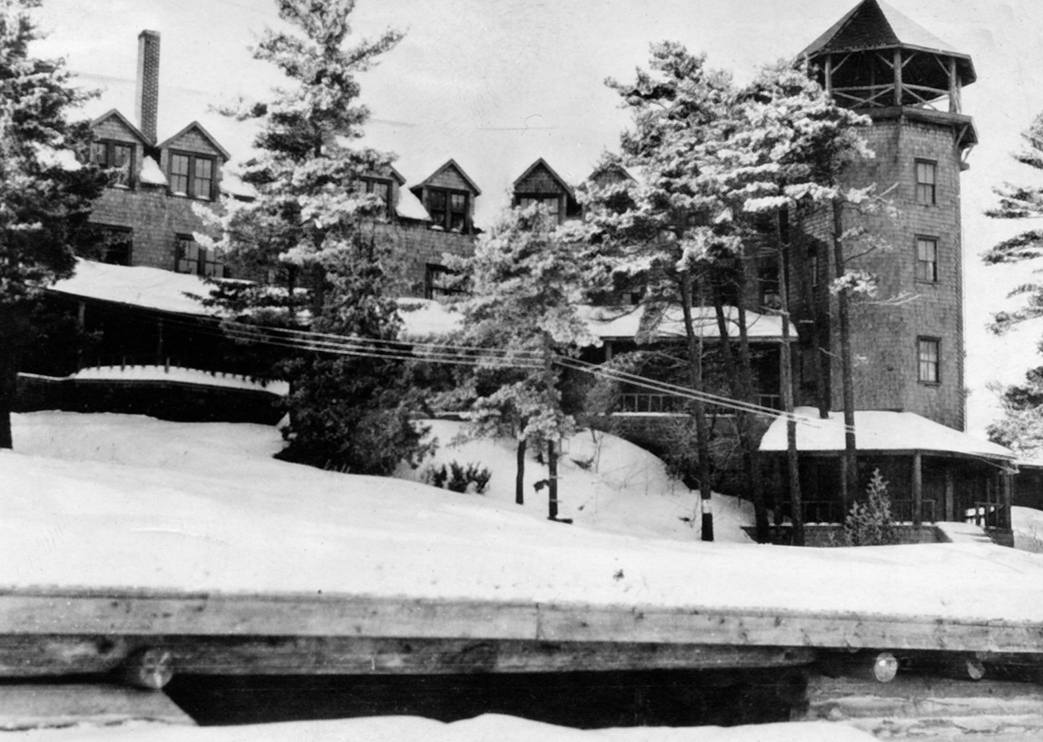

~

BEFORE THERE WERE REFRIGERATORS, EVERYTHING DEPENDED ON FILLING THE ICE HOUSES.

The best ice was blue. Hard and clean, it could usually be found in the bay in front of the Ojibway, and when it was 16 inches thick, the cutting could begin.

While calm, sunny days were surprisingly comfortable – even when the temperature dropped well below zero – the Ojibway’s ice crews learned to work through blizzards, freezing rain and high winds.

For many years, the Ojibway’s mechanic, Albert Desmasdon, was in charge and he hired a crew of 12 to 15 men. They stayed in the Ojibway’s cottages, and most winters the work would continue from just before Christmas until February. By then, the Ojibway’s two ice houses and the many others throughout Pointe au Baril were filled for the coming summer. When Bruce Reid started cutting ice for Albert in 1939, at 16 years of age, he earned two dollars a day.

It was Tanya MacLennan, the sister of Sondra, the young manager of the Ojibway throughout the 1950s, who said that for many years she thought a gin and tonic was a drink served with ice cubes, a wedge of lime and sawdust.

Albert Desmasdon (near left) organized the ice crews for the Ojibway. The men slept and ate in the hotel’s cottages and usually worked from December to February.

Getting in the ice was an important job. Taking a summer holiday at a cottage in Pointe au Baril in the days before propane refrigerators – to say nothing of running a busy hotel’s dining room, kitchen, butcher shop and grocery – was a good deal more difficult in the years when a mild winter made ice a scarce commodity. But usually the cold weather was reliable. Albert and his crew, staying as close to the hotel as possible, began by chopping a hole in the ice with an axe and then cutting a channel from the site on the bay they’d chosen to a spot about 30 feet from shore. With a long, large-toothed cross-cut saw, they carved out blocks that were 16 inches deep and wide and about two-and-a-half feet long. The blocks that were required by the Oldfields for the holds in their fishing tugs were a little longer – about three feet.

Usually, three men would be busy cutting the ice, and two others would push the blocks through the open channel with long hooked poles. A wooden slide had been built at the end of the channel, and using large tongs, two stalwart members of the crew hoisted the 100-to-200-pound blocks onto the slide. Once there, they were roped (Bruce Reid was renowned for his skill as an ice lassoer) and then they were hauled, two or three blocks at a time, up the slide to the ice house, by a single horse or sometimes by a team of horses. Ice that was destined for the Oldfields, or Kennedy’s store, or for the ice houses out on cottagers’ islands was hauled across the frozen bay on a horse-drawn sleigh. The ice was piled on a large crib built between the sleigh’s rounded 20-foot-long runners.

At the ice house, the blocks were stacked one completed level at a time. It was like laying a floor over and over. About a foot of space was maintained between the ice and the walls of an ice house, and once the ice house was stacked, sawdust was packed into the gap between ice and wall for insulation. It was Tanya MacLennan, the sister of Sondra, the young manager of the Ojibway throughout the 1950s, who said that for many years, she thought a gin and tonic was a drink that was always served with ice cubes, a wedge of lime and sawdust.

Working the ice with Albert Desmasdon was a tough job. Albert knew that working in the dead of winter, whatever the conditions, was vastly preferable to working later in the season when the ice was softening. An early thaw was always unlikely during a Pointe au Baril winter, but Albert operated as if one were around the corner. So his crews learned to work with great efficiency: the process of cutting, floating, hauling and stacking the blocks of ice was a precise assembly line of activity. Nobody slacked off. Albert’s crew also became accustomed to working through snow, rain, sleet, wind and rattling blizzards. Surprisingly, the bitter cold was not always a factor. As Bruce Reid recalled of his winter days hauling ice: “It could be 40 below zero, but when it was sunny we didn’t really feel the cold because we were always working so hard.”